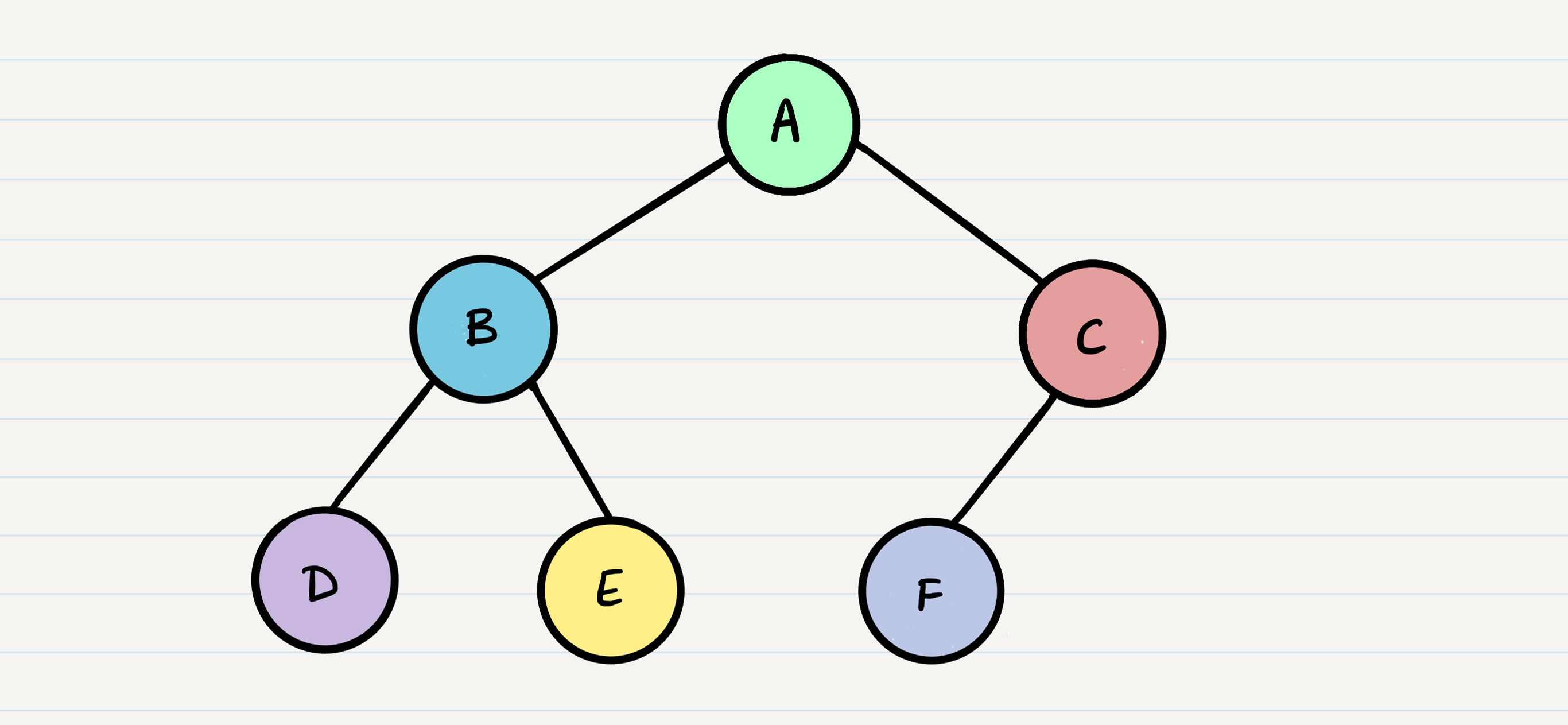

Trees

In this tutorial, we’ll be covering Binary Trees, Binary Search Trees, and K-ary Trees. We will review some common terminology that is shared amongst all of the trees and then dive into specifics of the different types.

Common Terminology

Node - A Tree node is a component which may contain it’s own values, and references to other nodes Root - The root is the node at the beginning of the tree K - A number that specifies the maximum number of children any node may have in a k-ary tree. In a binary tree, k = 2. Left - A reference to one child node, in a binary tree Right - A reference to the other child node, in a binary tree Edge - The edge in a tree is the link between a parent and child node Leaf - A leaf is a node that does not have any children Height - The height of a tree is the number of edges from the root to the furthest leaf

Traversals

An important aspect of trees is how to traverse them. Traversing a tree allows us to search for a node, print out the contents of a tree, and much more! There are two categories of traversals when it comes to trees:

Depth First

Breadth First

Depth First

Depth first traversal is where we prioritize going through the depth (height) of the tree first. There are multiple ways to carry out depth first traversal, and each method changes the order in which we search/print the root. Here are three methods for depth first traversal:

- Pre-order: root » left » right

- In-order: left » root » right

- Post-order: left » right » root

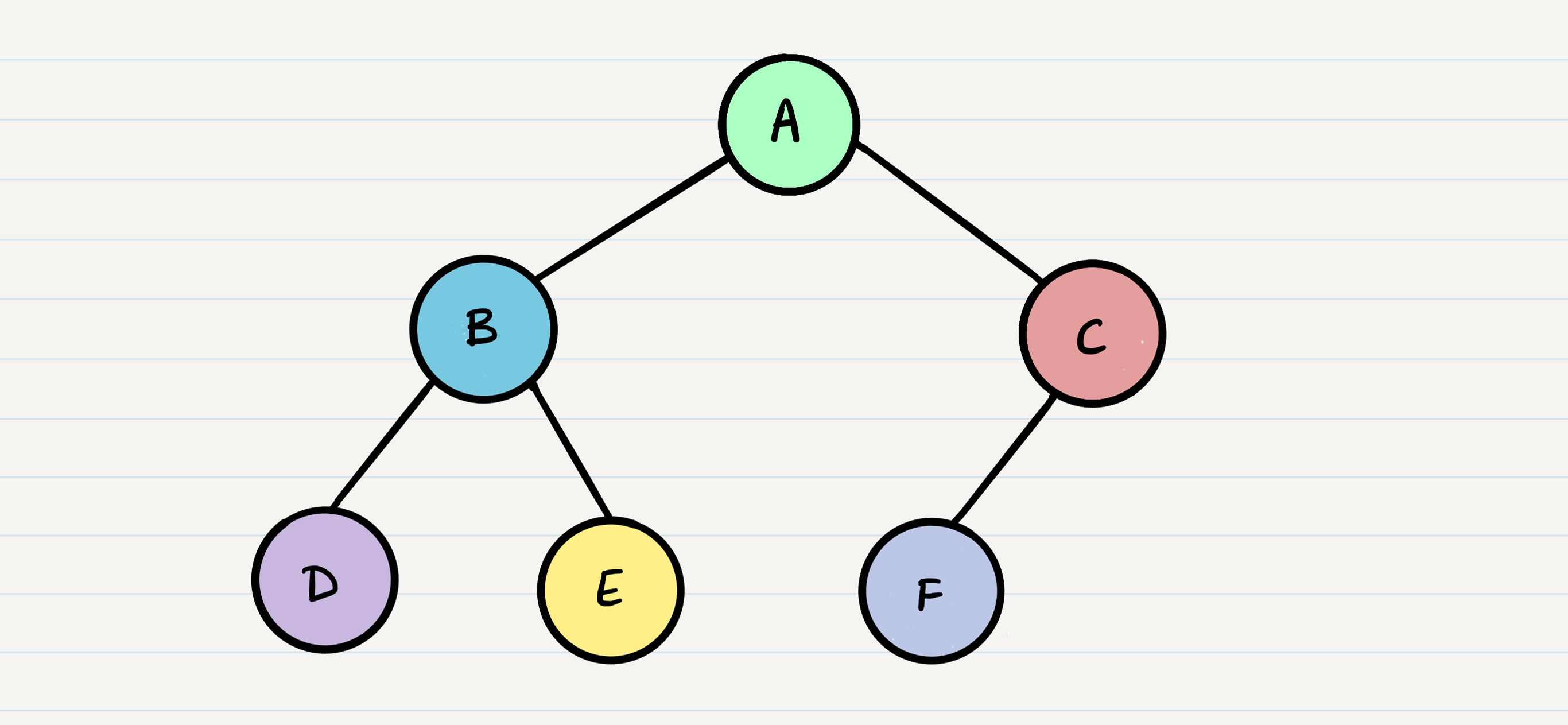

Given the sample tree above, our traversals would result in different paths:

- Pre-order: A, B, D, E, C, F

- In-order: D, B, E, A, F, C

- Post-order: D, E, B, F, C, A

The most common way to traverse through a tree is to use recursion. With these traversals, we rely on the call stack to navigate back up the tree when we have reached the end of a sub-path.

Pre-order

Let’s break down the pre-order traversal. Here is the pseudocode for this traversal method:

ALGORITHM preOrder(root)

OUTPUT <-- root.value

if root.left is not NULL

preOrder(root.left)

if root.right is not NULL

preOrder(root.right)

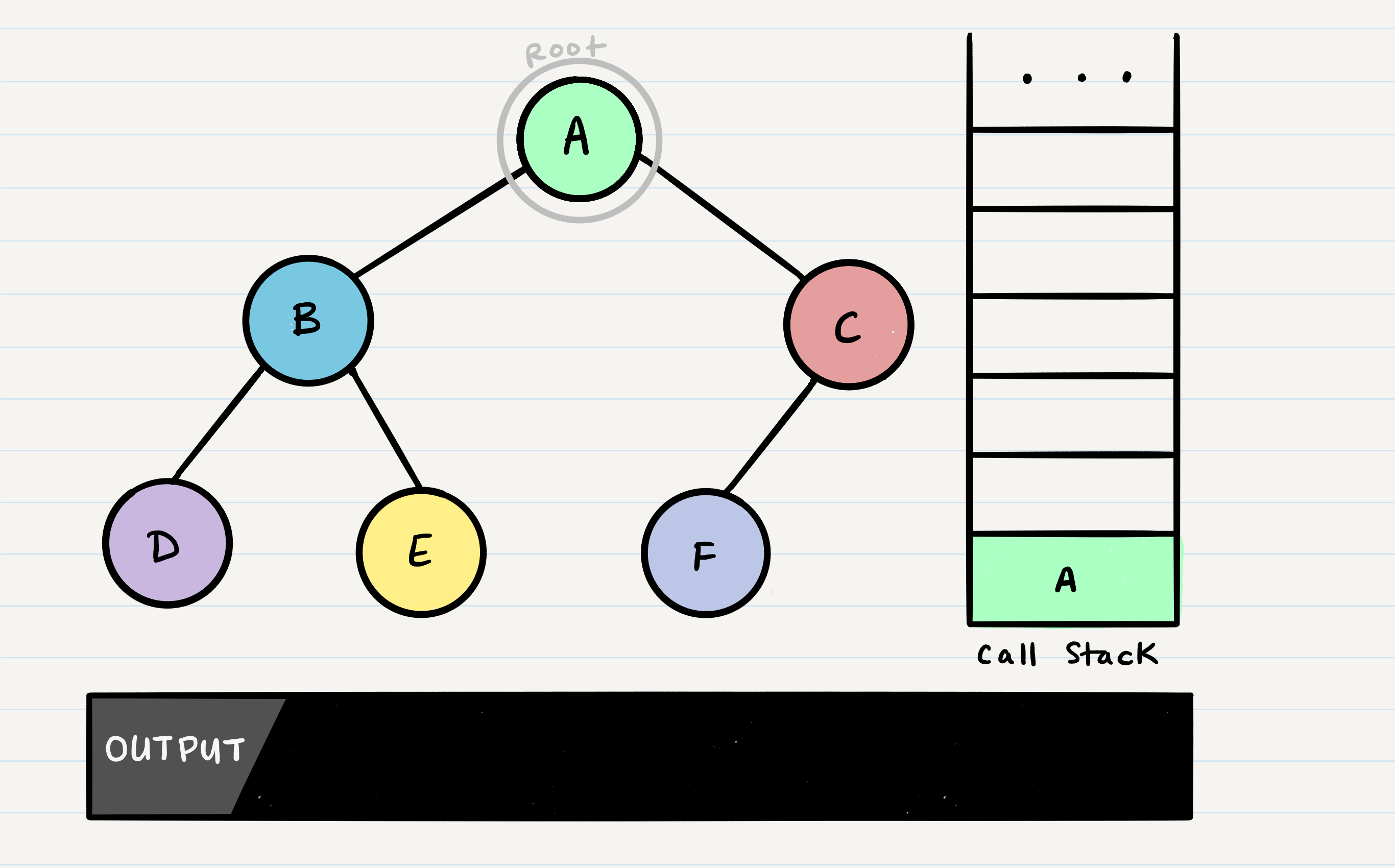

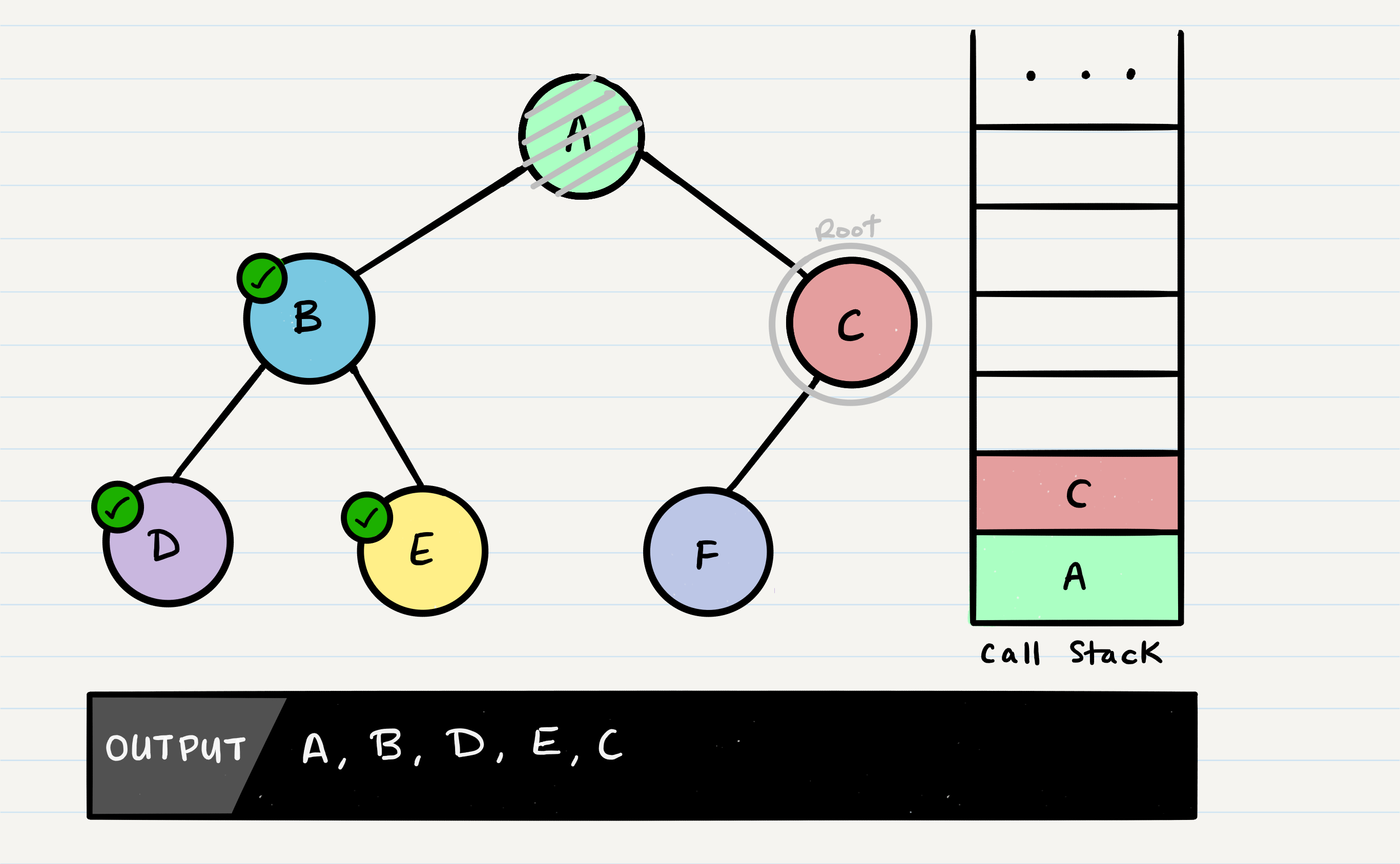

Pre-order means that the root has to be looked at first. In our case, looking at the root just means that we output its value. When we call preOrder for the first time, the root will be added to the call stack:

Next, we start reading our preOrder function’s code from top to bottom. The first line of code reads this:

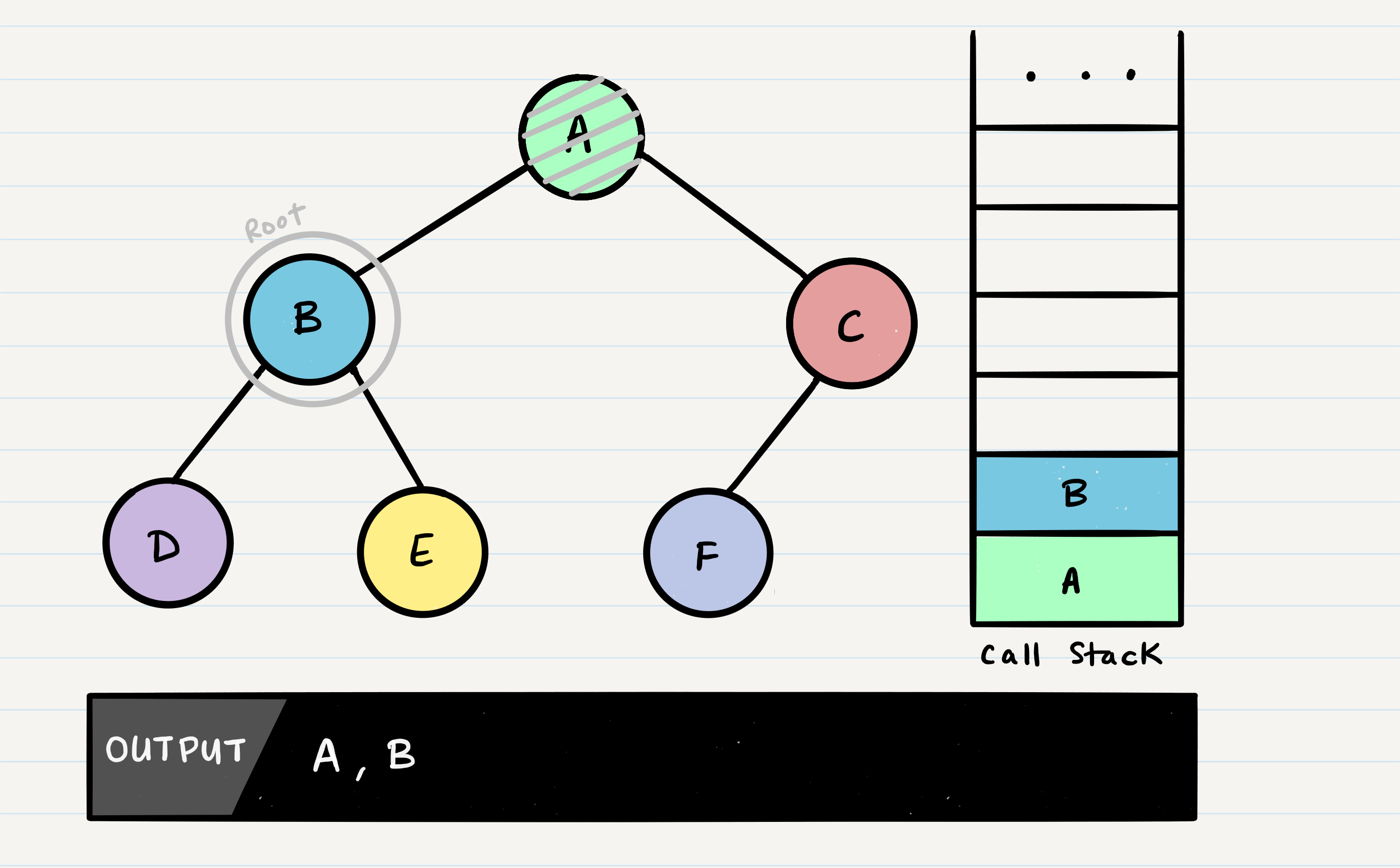

OUTPUT <– root.value This means that we will output the root.value out to the console. Then, our next block of code instructs us to check if our root has a left node set. If the root does, we will then send the left node to our preOrder method recursively. This means that we make another function call, where B is our new root:

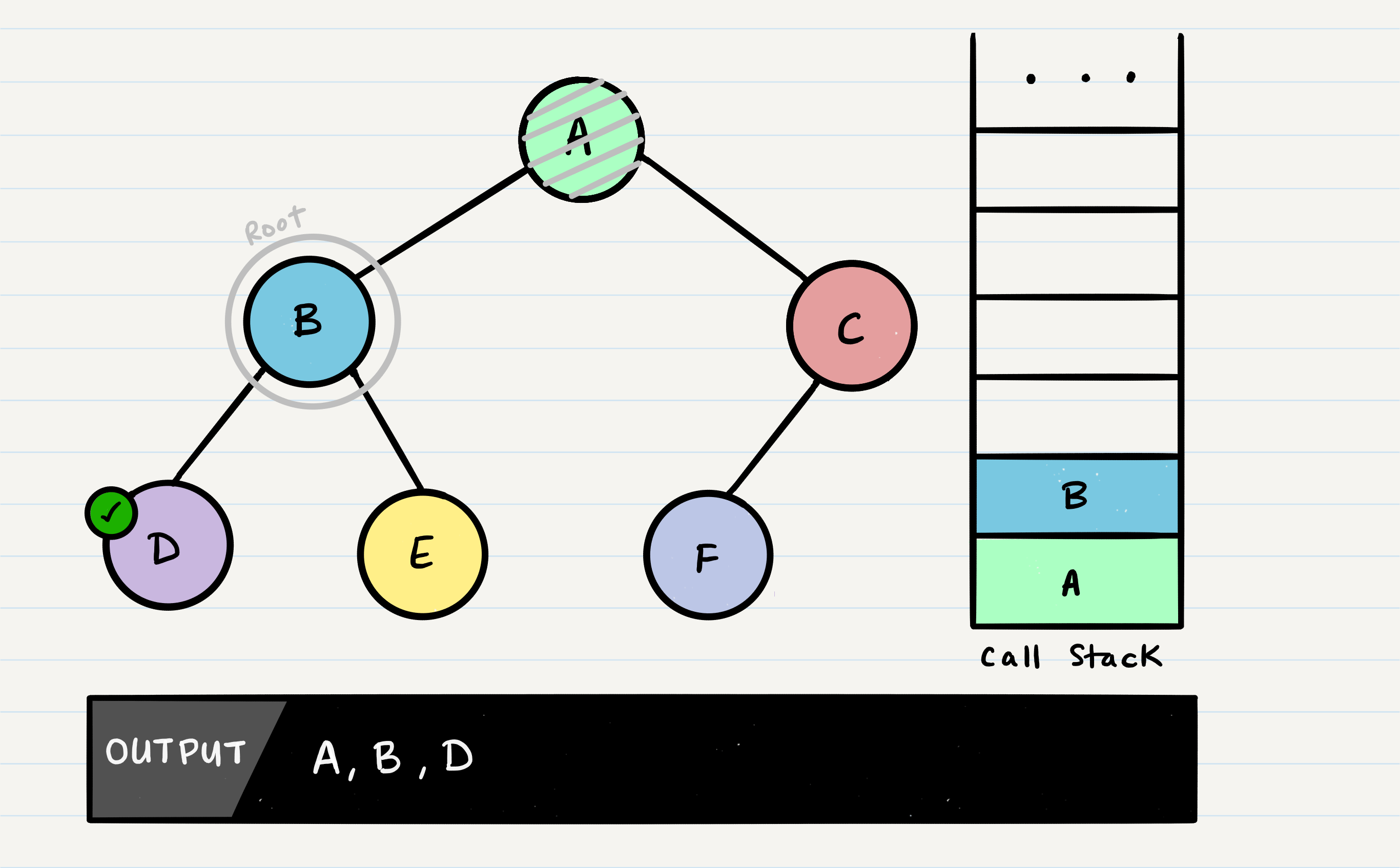

This process continues until we reach a leaf node. Here’s the state of our tree when we hit our first leaf, D:

It’s important to note a few things that are about to happen:

The program will look for both a root.left and a root.right. Both will return null, so it will end the execution of that method call D will pop off of the call stack and the root will be reassigned back to B This is the heart of recursion: when we complete a function call, we pop it off the stack and are able to continue execution through the previous function call

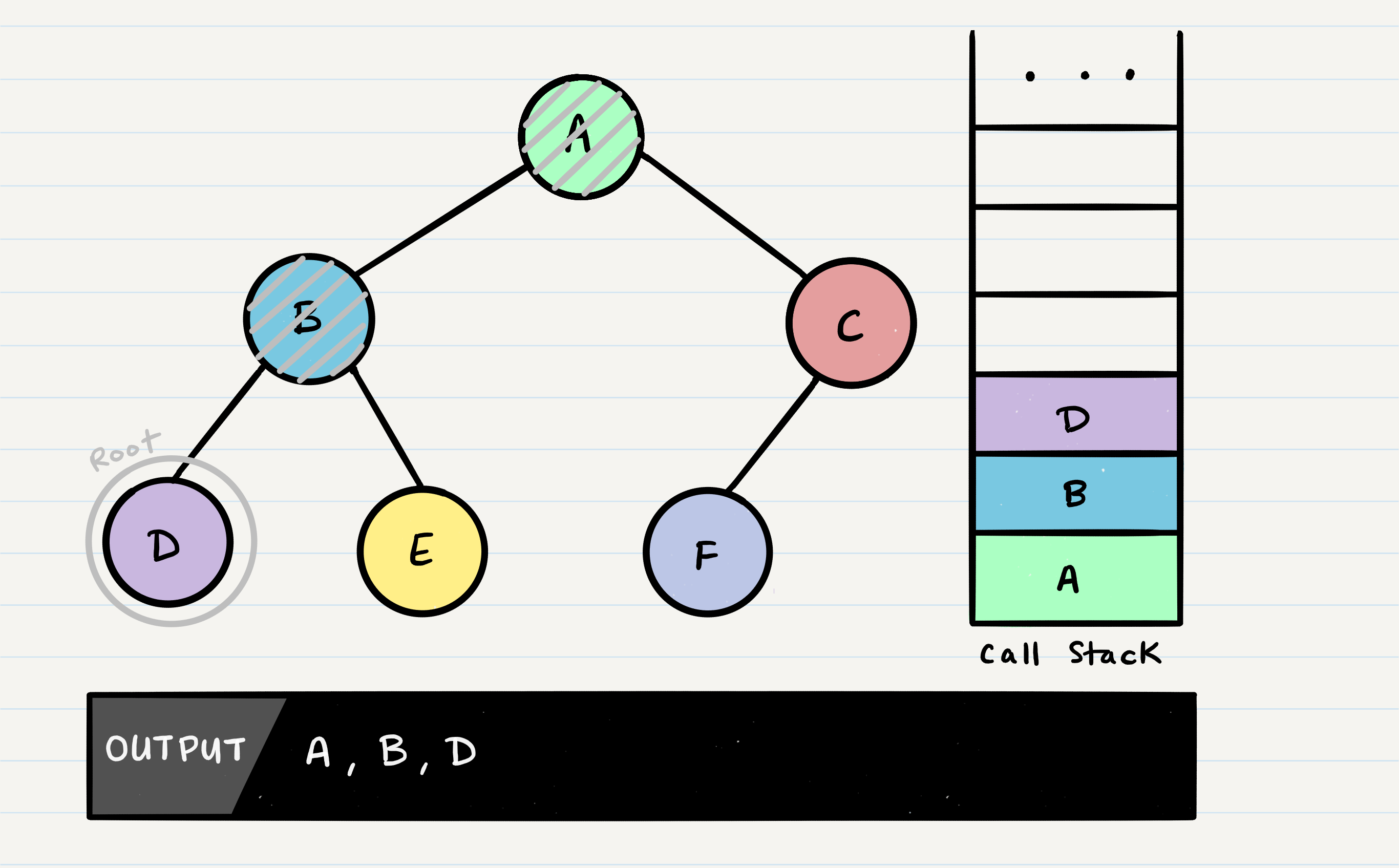

The code block will now pick up where it left off when B was the root. Since it already looked for root.left, it will now look for root.right.

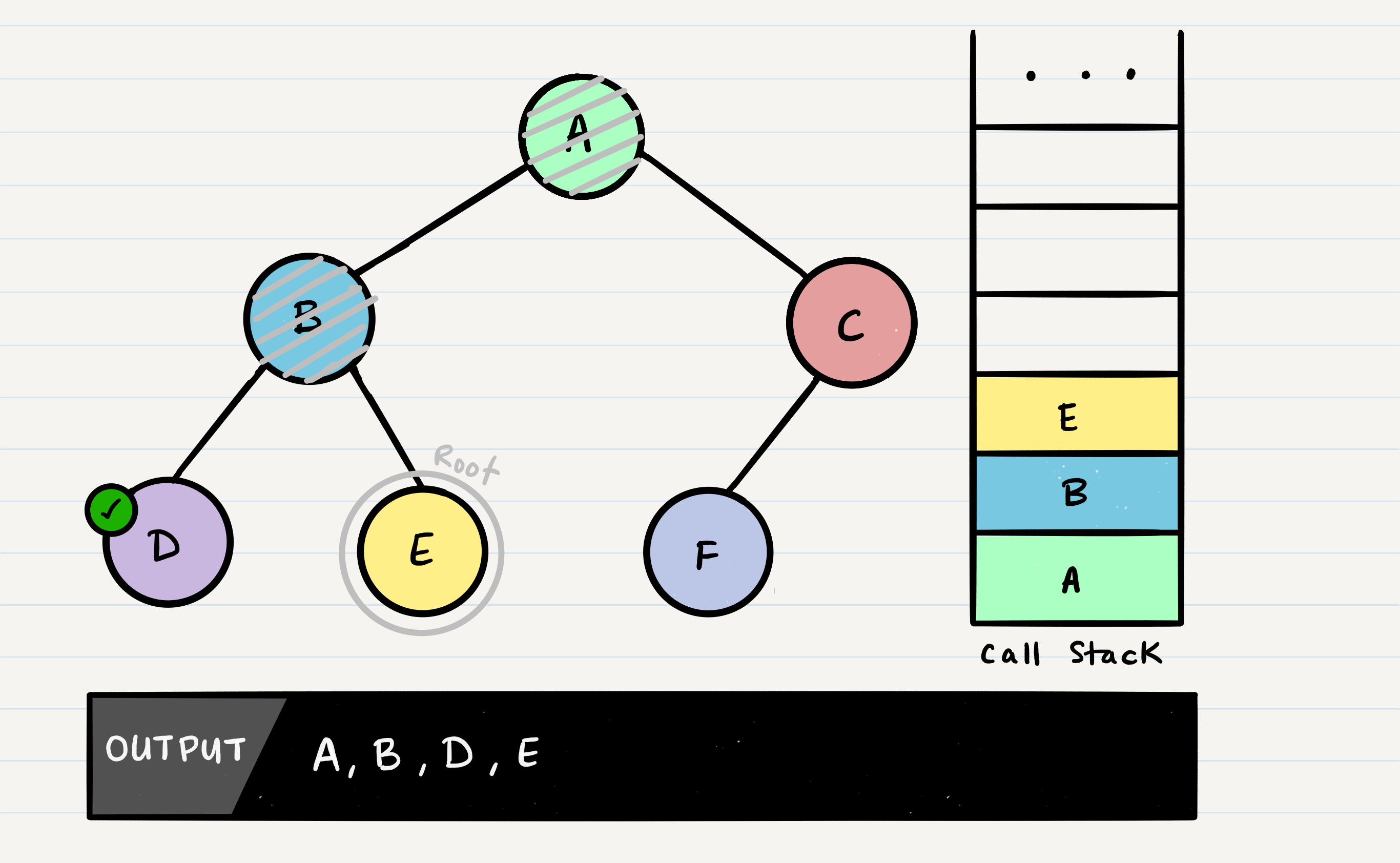

E will output to the console. Since E is a leaf, it will complete the method code block, and pop E off of the call stack and make its way back up to B.

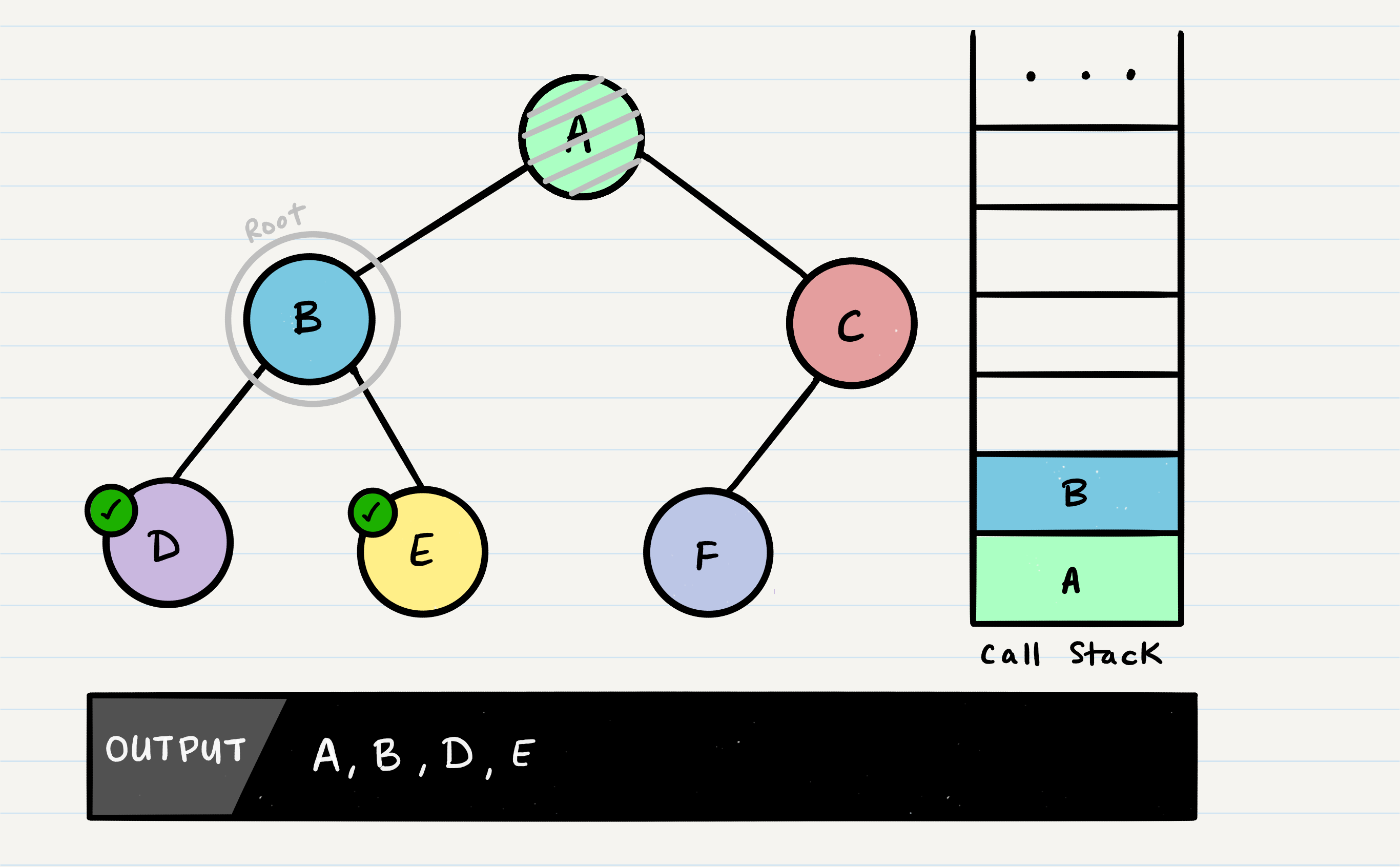

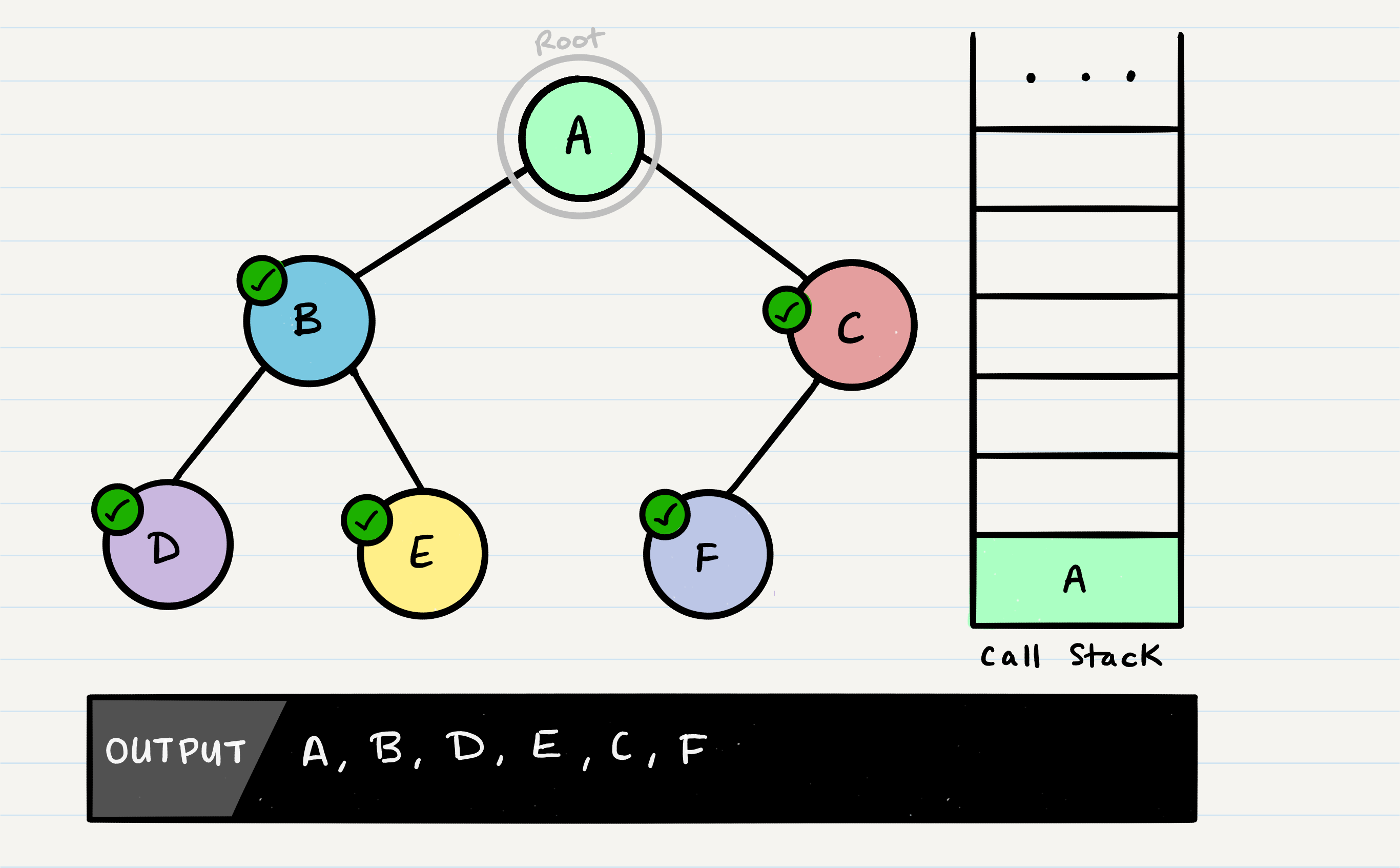

In the function call, B has already checked for root.left, and root.right. There are no further lines of code to execute, so B will be popped off the call stack, so that we can resume execution of A.

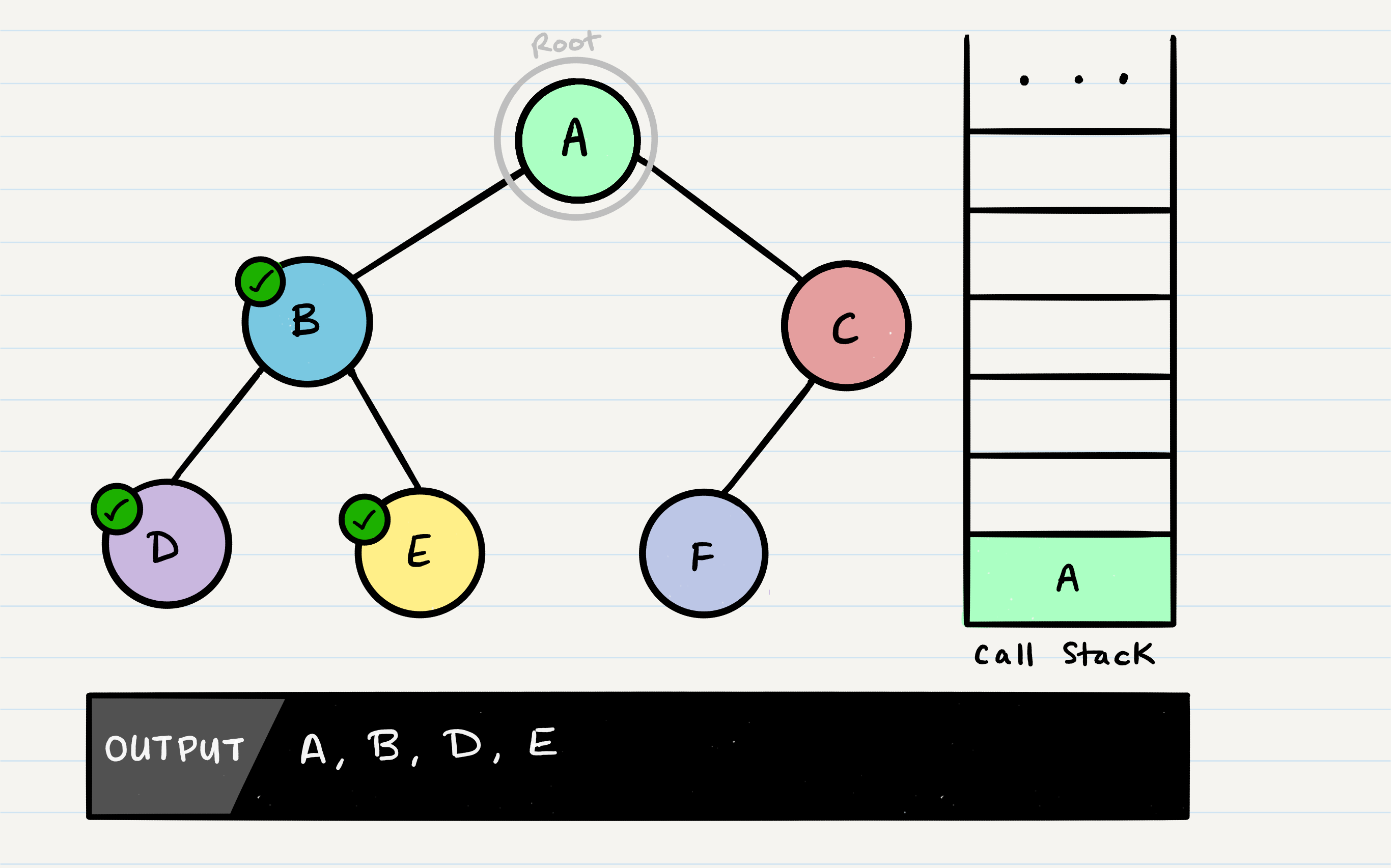

Following the same pattern as we did with the other nodes, A’s call stack frame will pick up where it left off, and check out root.right. C will be added to the call stack frame, and it will the new function’s root.

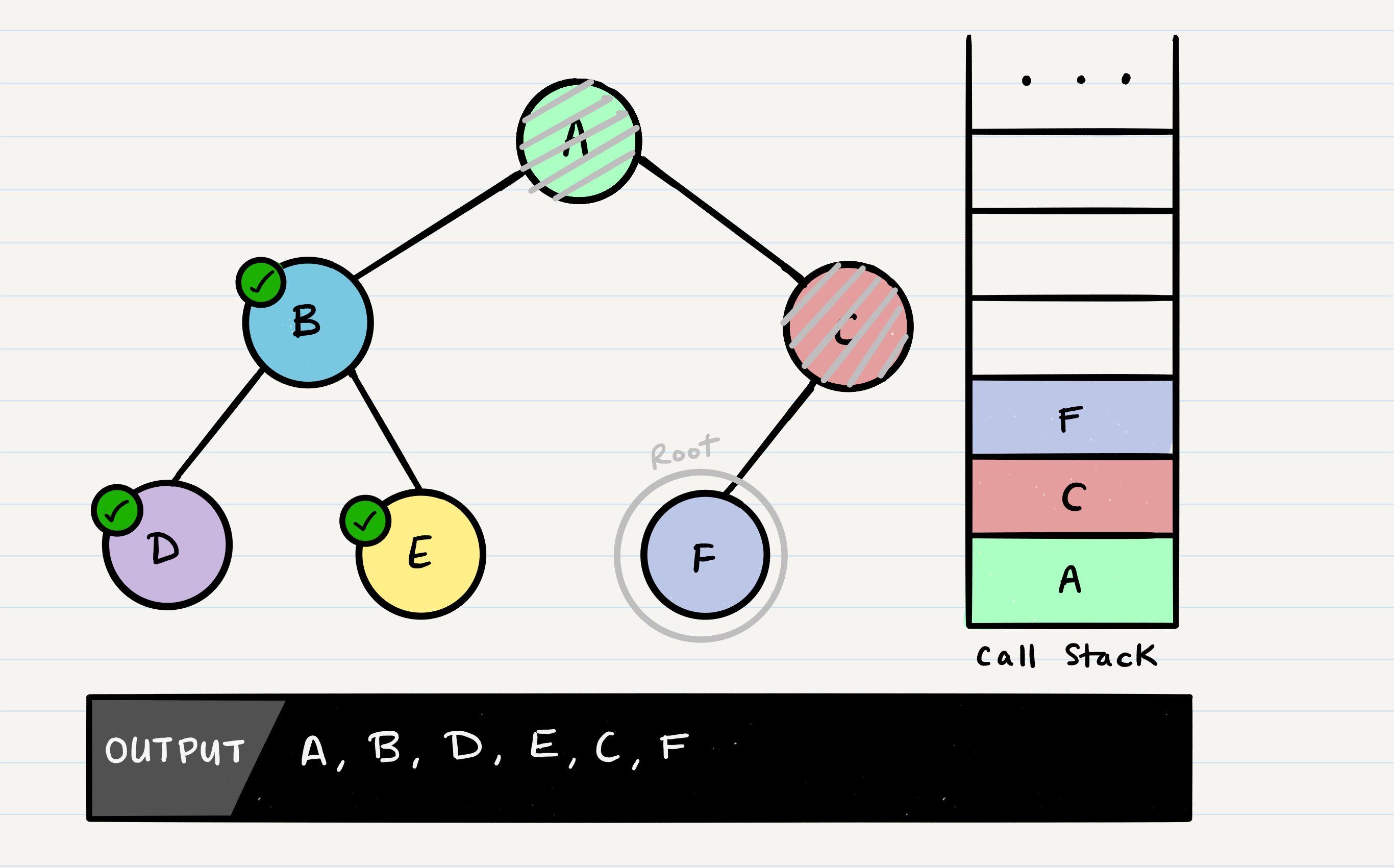

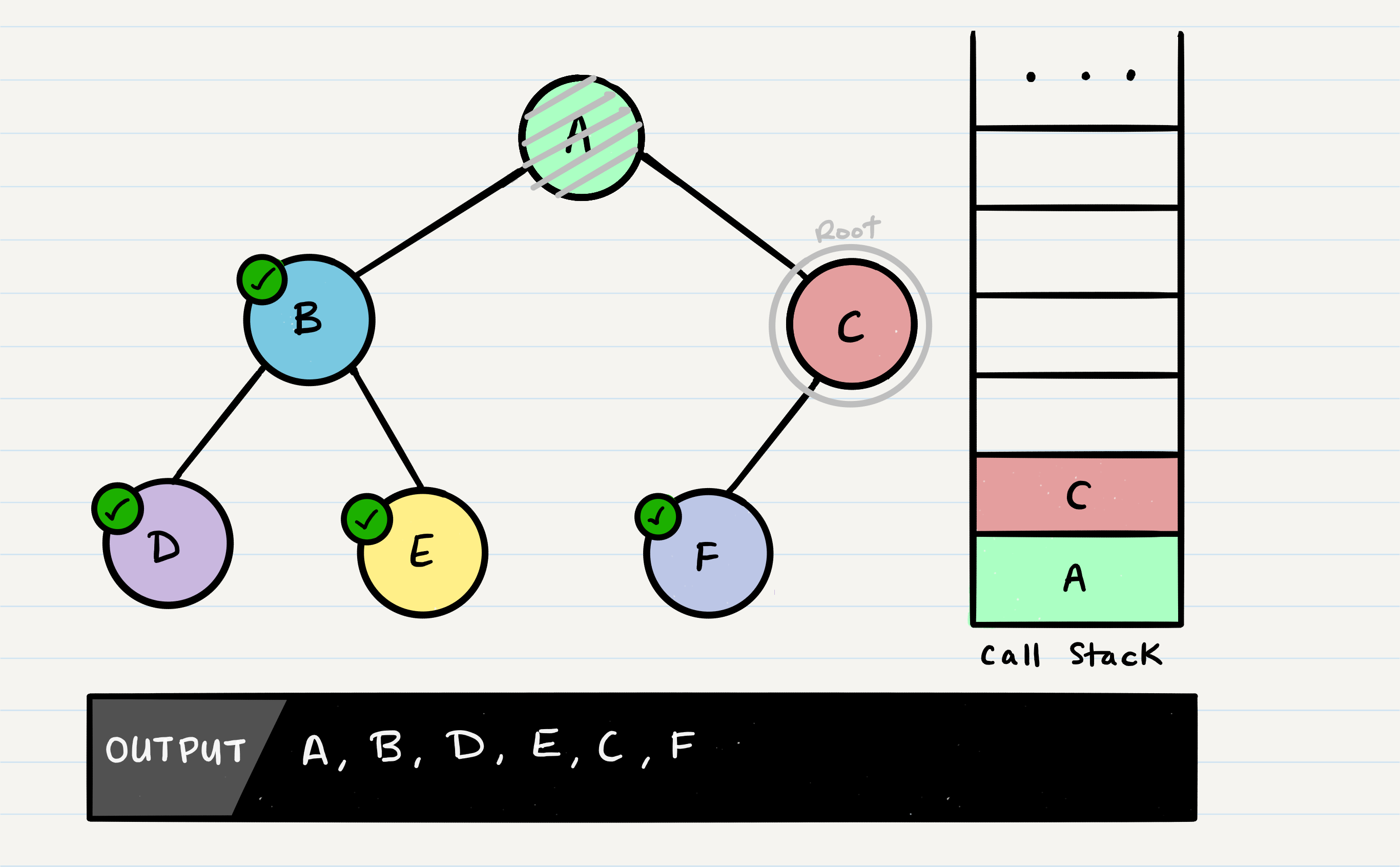

C will be outputted to the console, and root.left will be evaluated. Because C has a left child, preOrder will be called, with the parameter root.left.

At this point, the program will find that F does not have any children and it will make its way back up the call stack up to C.

C does not have a root.right, so it will pop off the call stack and return to A.

Congratulations! Your pre-order traversal is completed!

Traversal Pseudocode

Here is the pseudocode for all three of the depth first traversals:

Pre-order

ALGORITHM preOrder(root)

// INPUT <-- root node

// OUTPUT <-- pre-order output of tree node's values

OUTPUT <-- root.value

if root.left is not Null

preOrder(root.left)

if root.right is not NULL

preOrder(root.right)

In-order

ALGORITHM inOrder(root)

// INPUT <-- root node

// OUTPUT <-- in-order output of tree node's values

if root.left is not NULL

inOrder(root.left)

OUTPUT <-- root.value

if root.right is not NULL

inOrder(root.right)

Post-order

ALGORITHM postOrder(root)

// INPUT <-- root node

// OUTPUT <-- post-order output of tree node's values

if root.left is not NULL

postOrder(root.left)

if root.right is not NULL

postOrder(root.right)

OUTPUT <-- root.value

Notice the similarities between the three different traversals above. The biggest difference between each of the traversals is when you are looking at the root node.

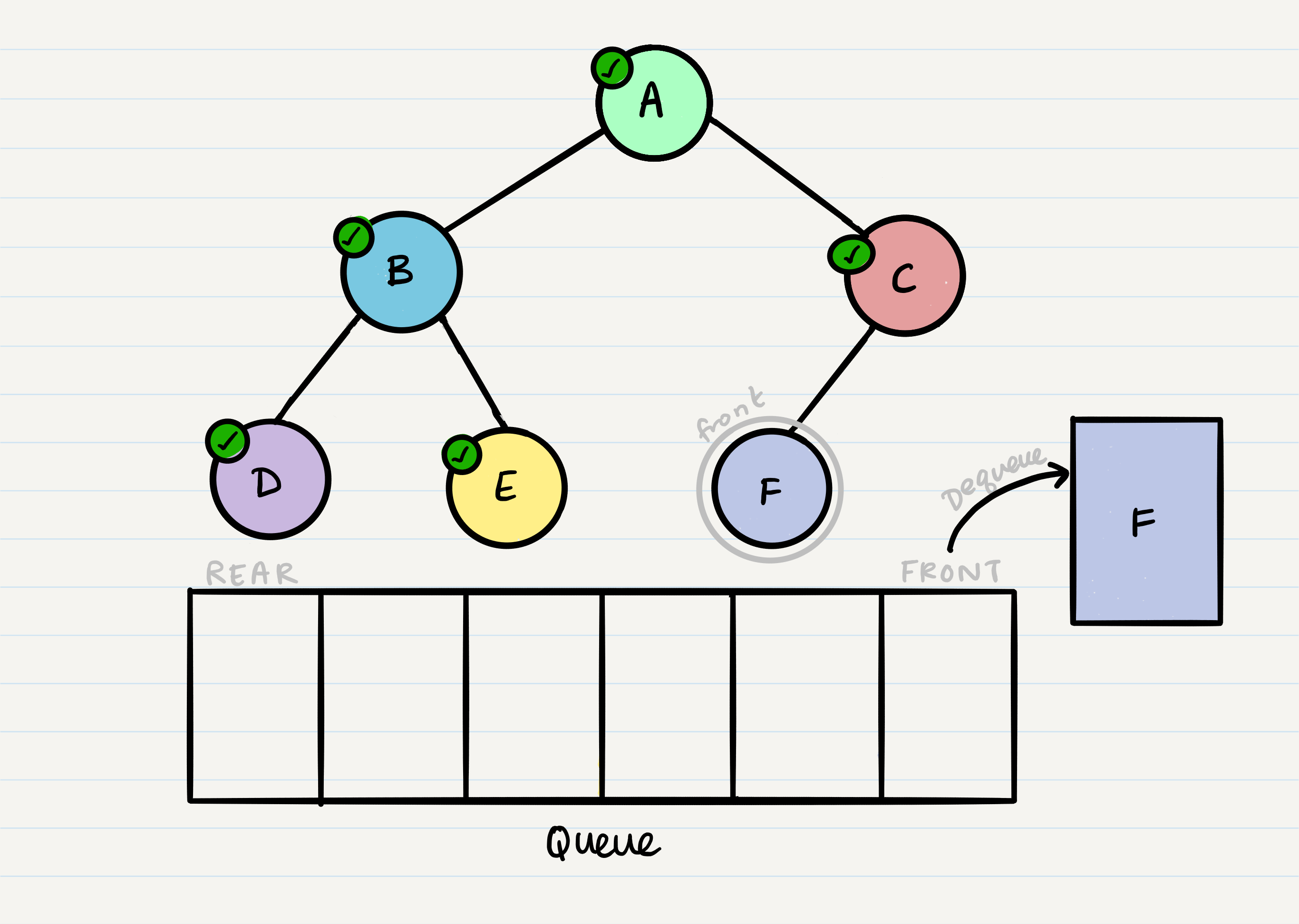

Breadth First

Breadth first traversal iterates through the tree by going through each level of the tree node-by-node. So, given our starting tree one more time:

Our output using breadth first traversal is now:

Output: A, B, C, D, E, F

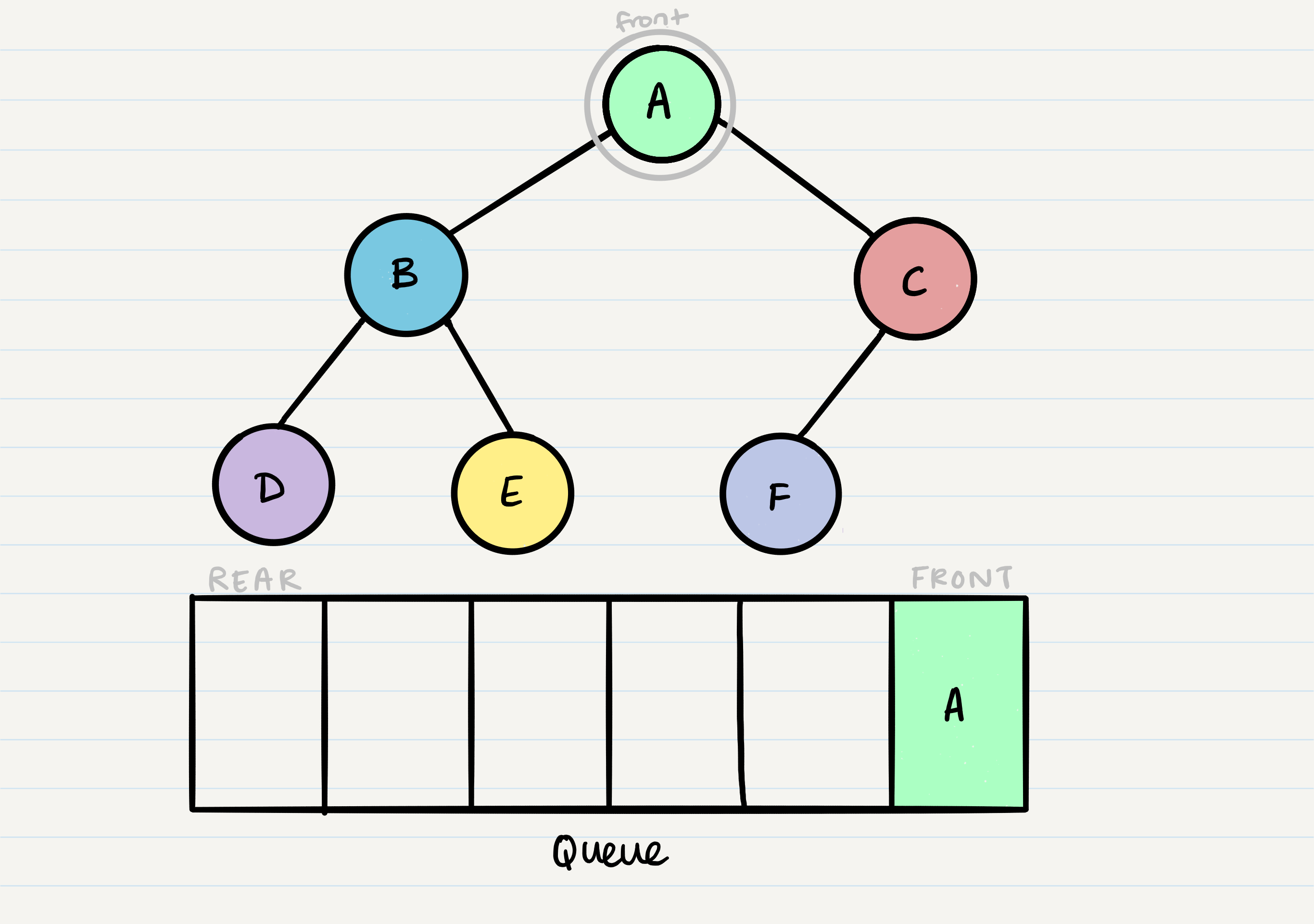

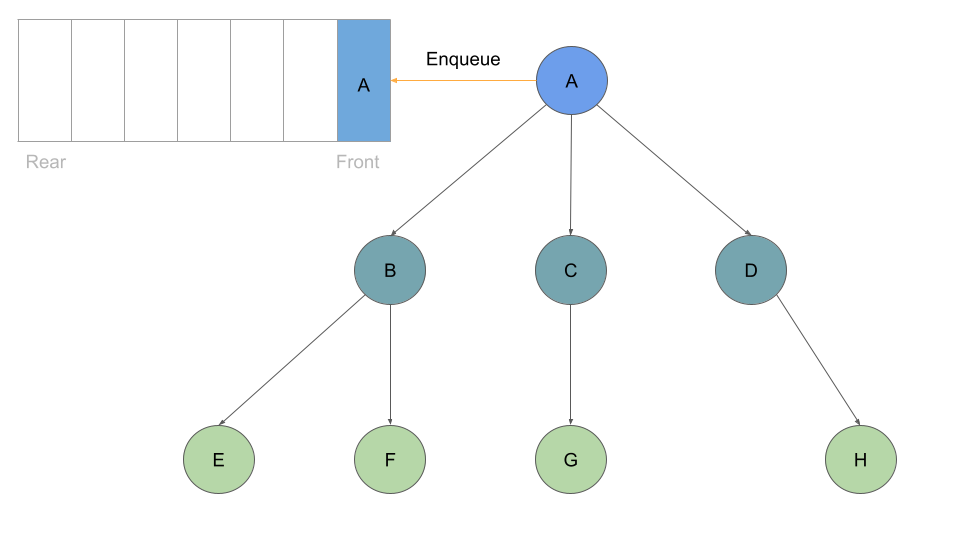

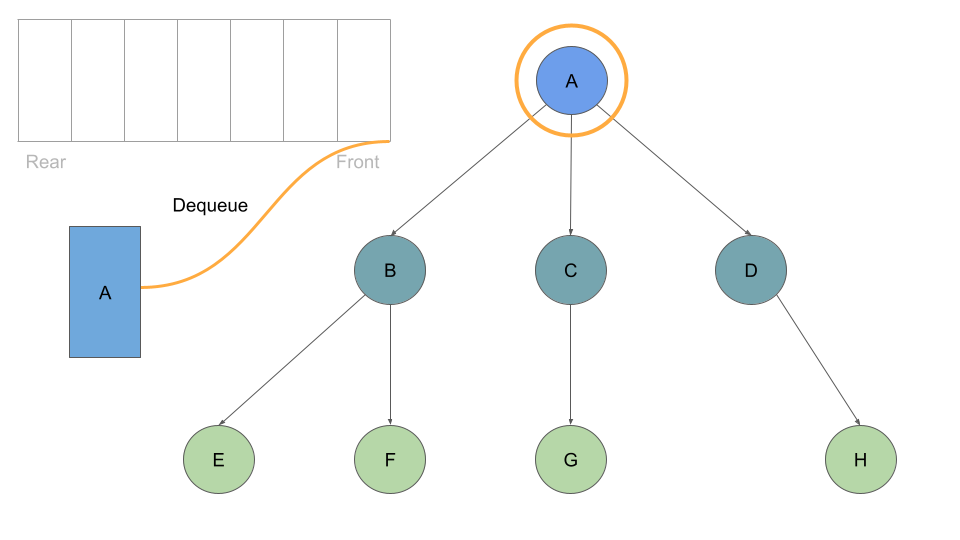

Traditionally, breadth first traversal uses a queue (instead of the call stack via recursion) to traverse the width/breadth of the tree. Let’s break down the process.

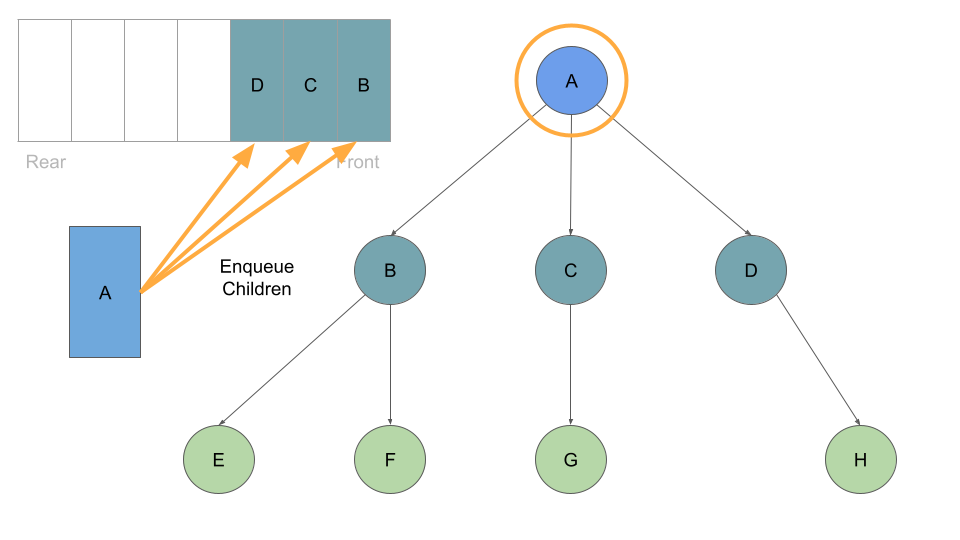

Given our starting tree shown above, let’s start by putting the root into the queue:

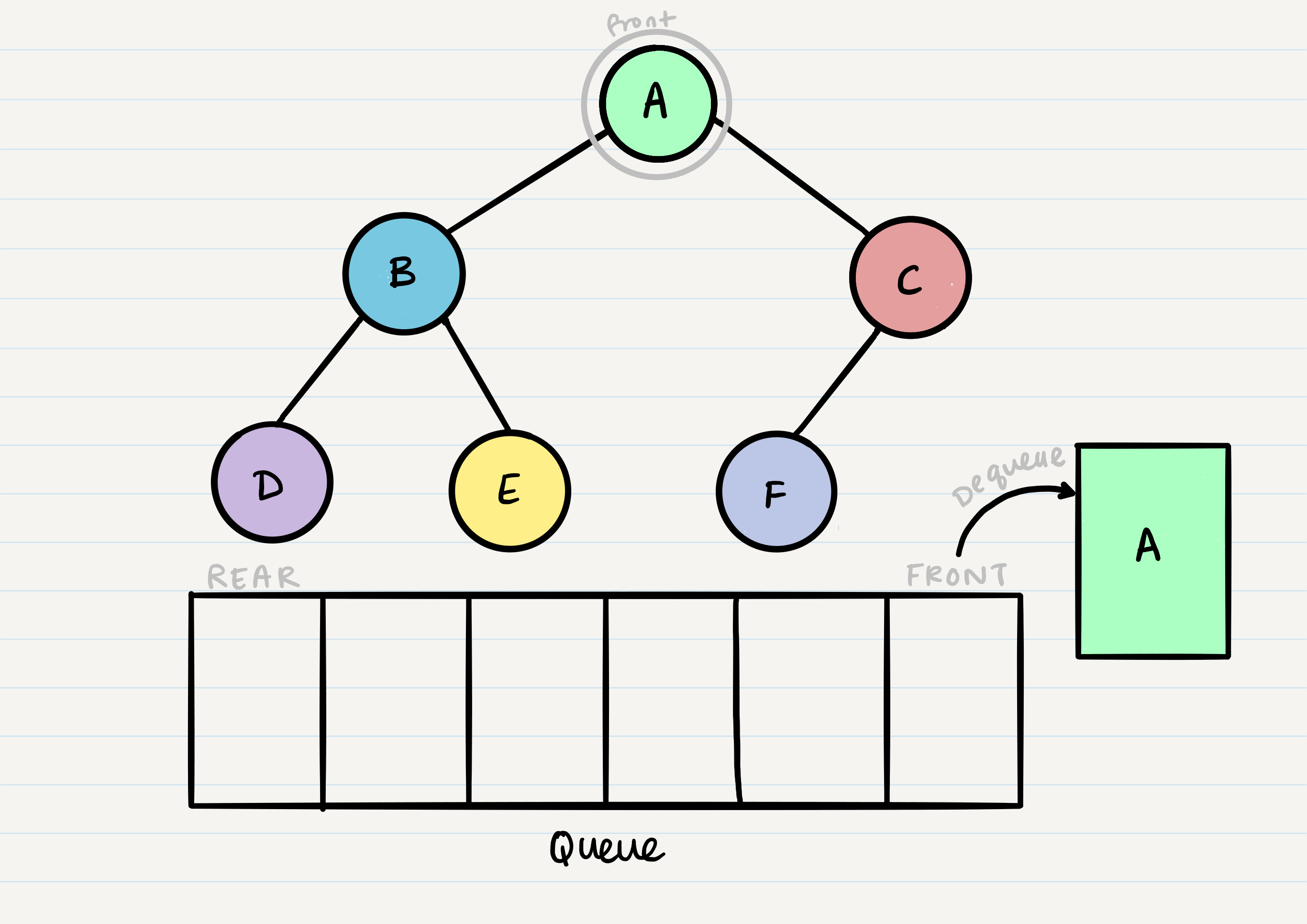

Now that we have one node in our queue, we can dequeue it and use that node in our code.

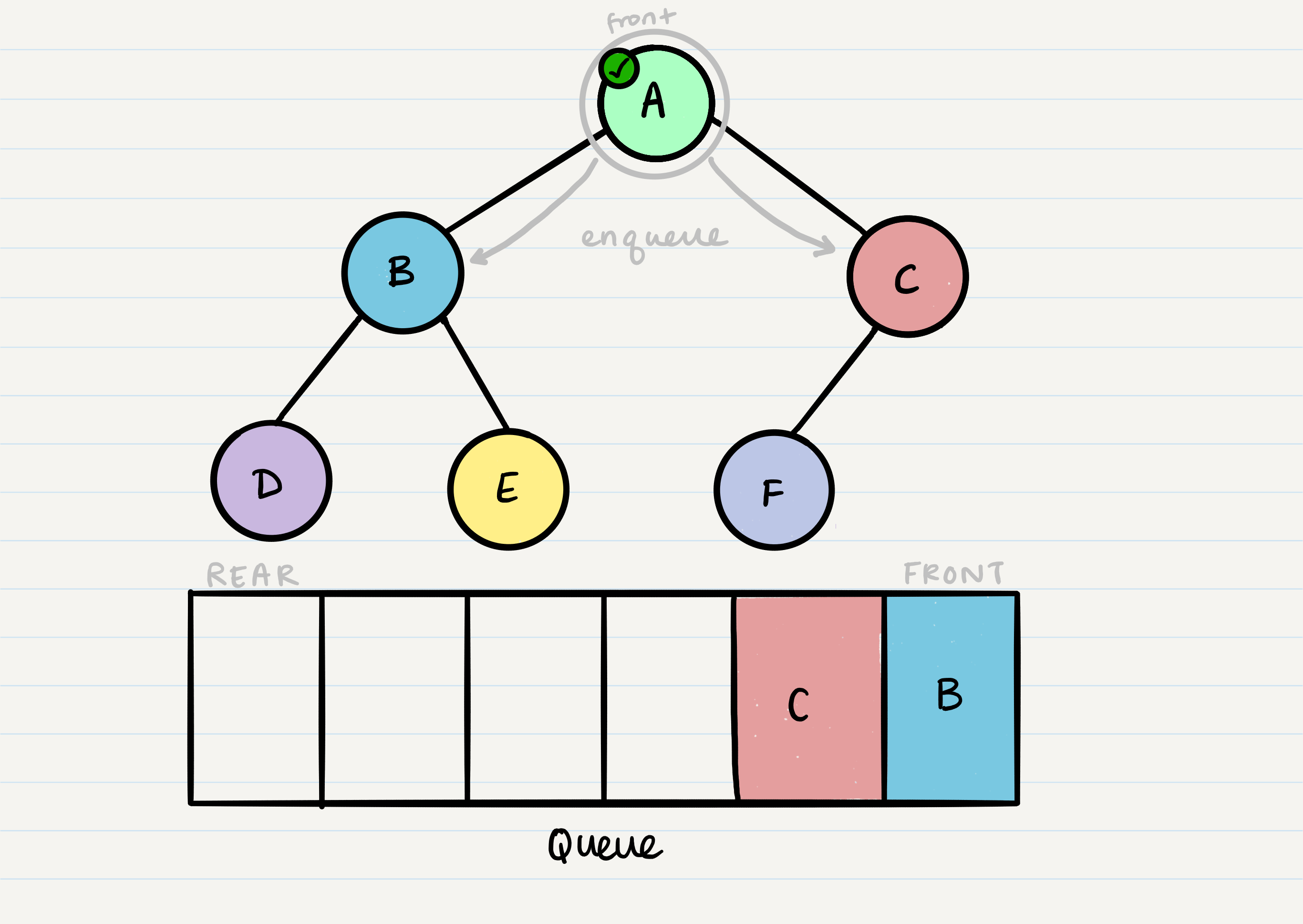

From our dequeued node A, we can enqueue the left and right child (in that order).

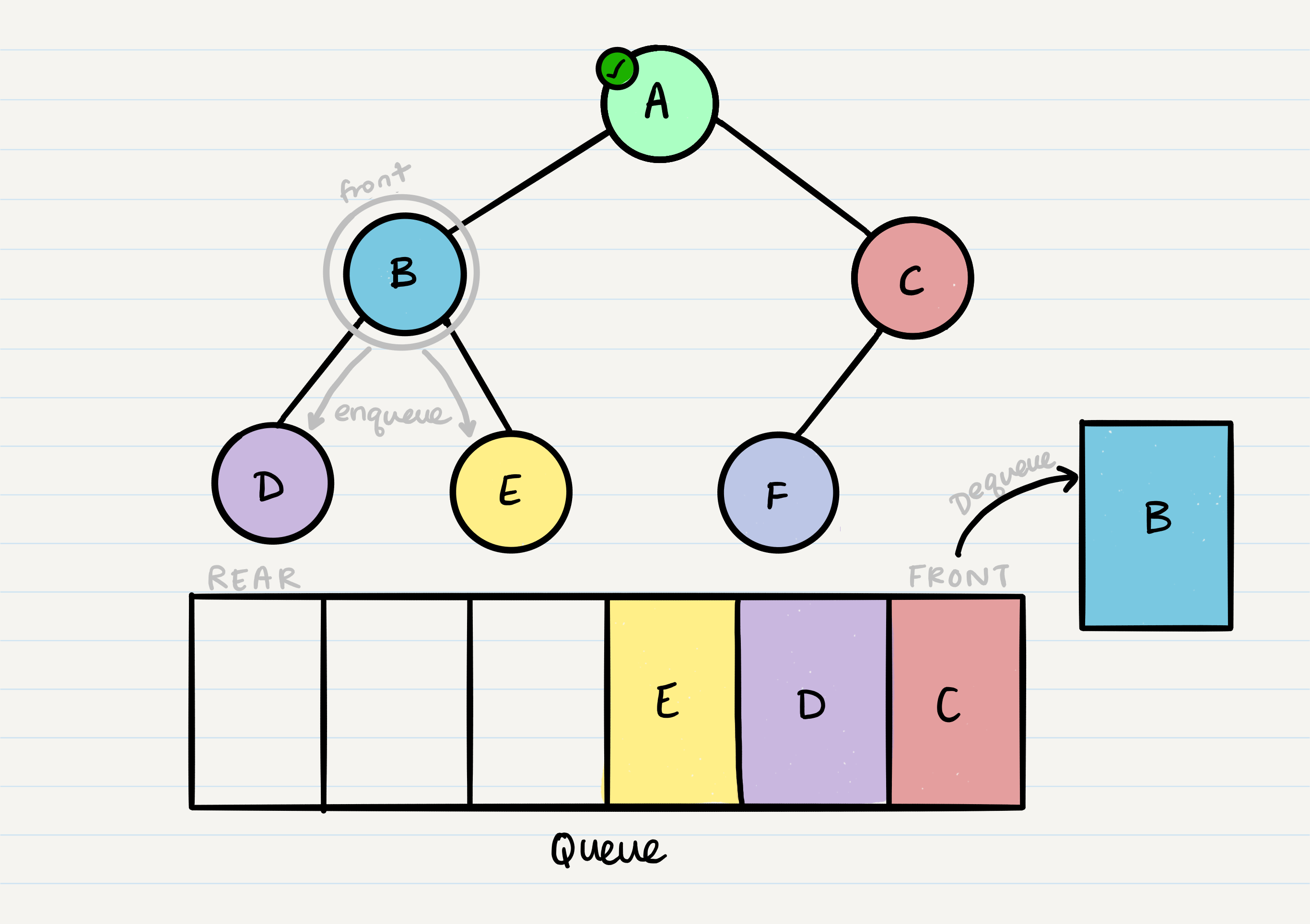

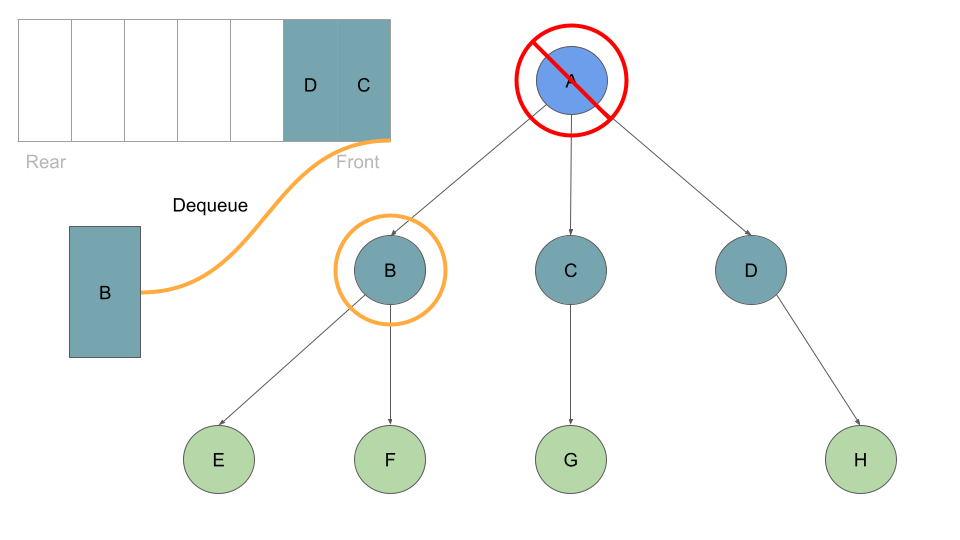

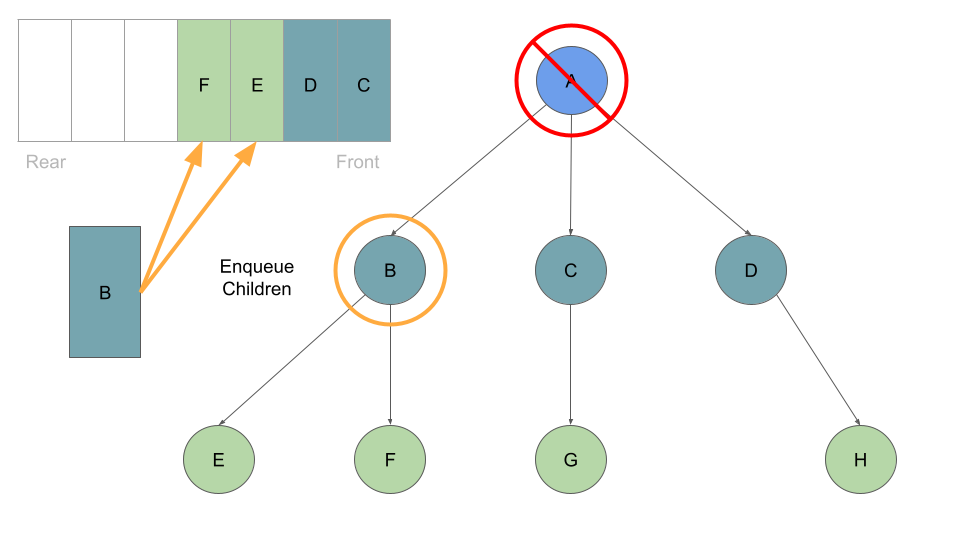

This leaves us with B as the new front of our queue. We can then repeat the process we did with A: Dequeue the front node, enqueue that node’s left and right nodes, and move to the next new front of the queue.

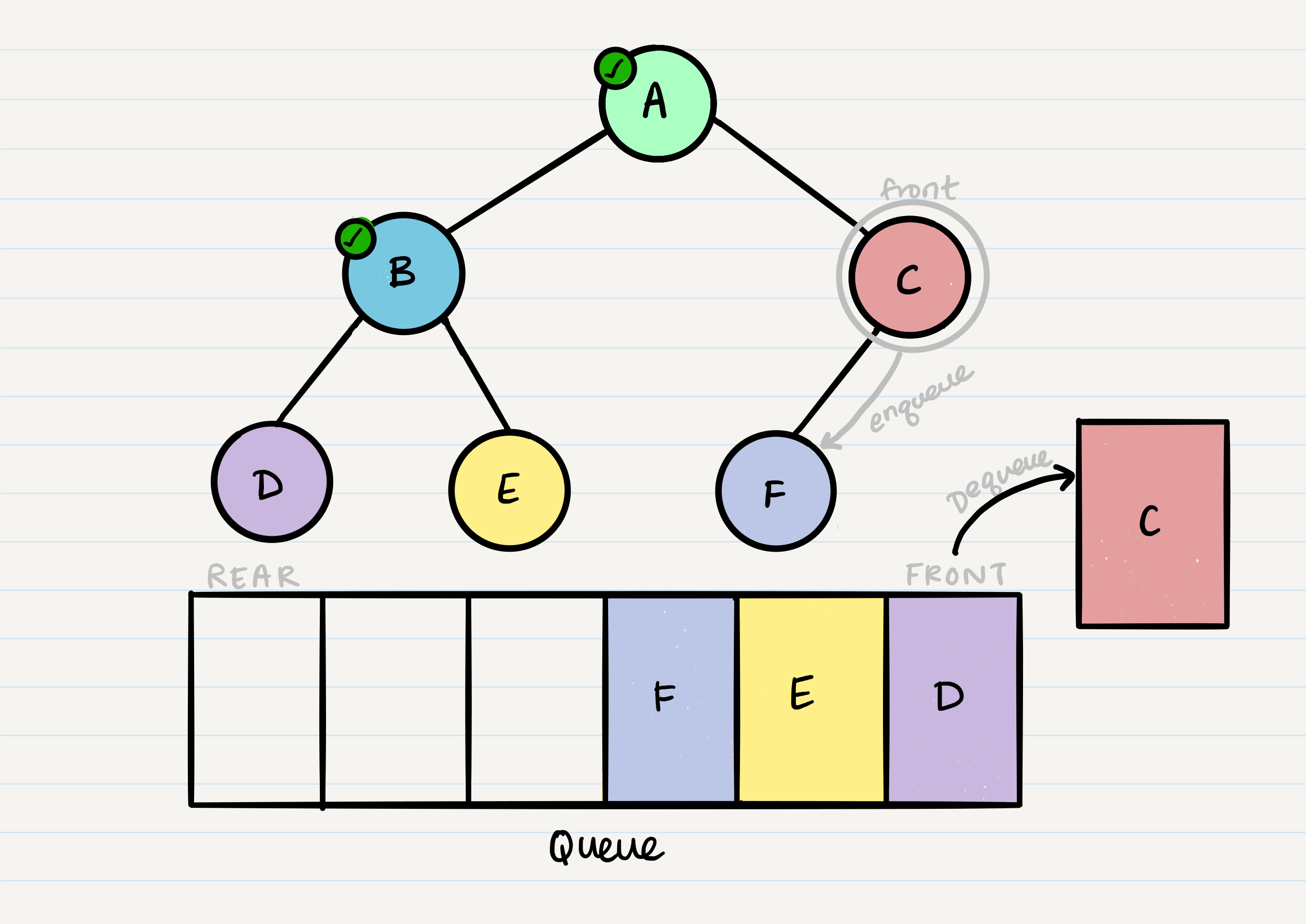

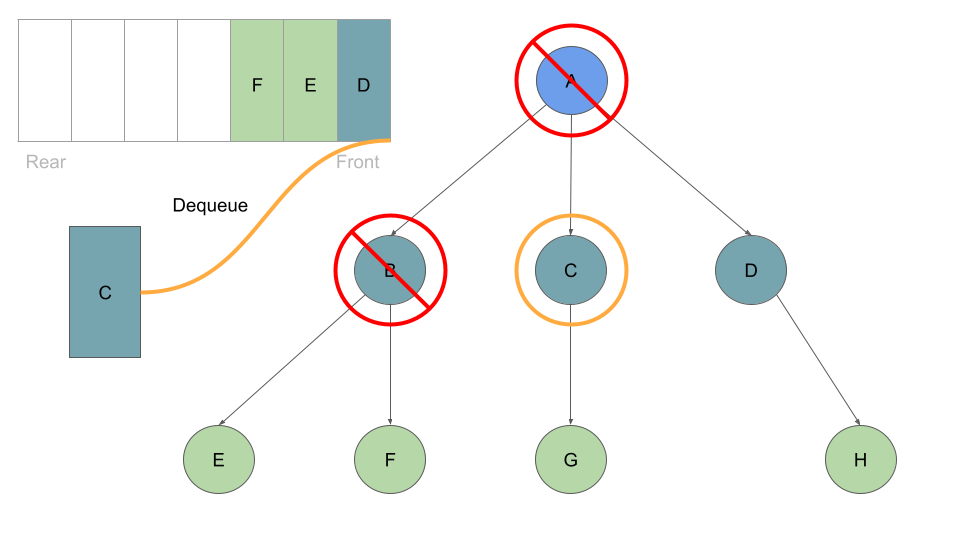

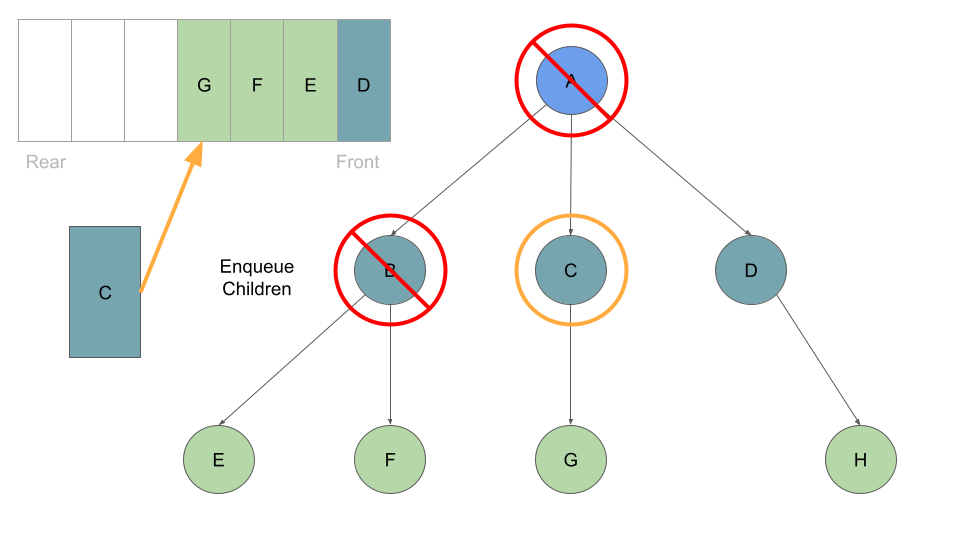

Now our front is C, so we repeat the dequeue + enqueue children process:

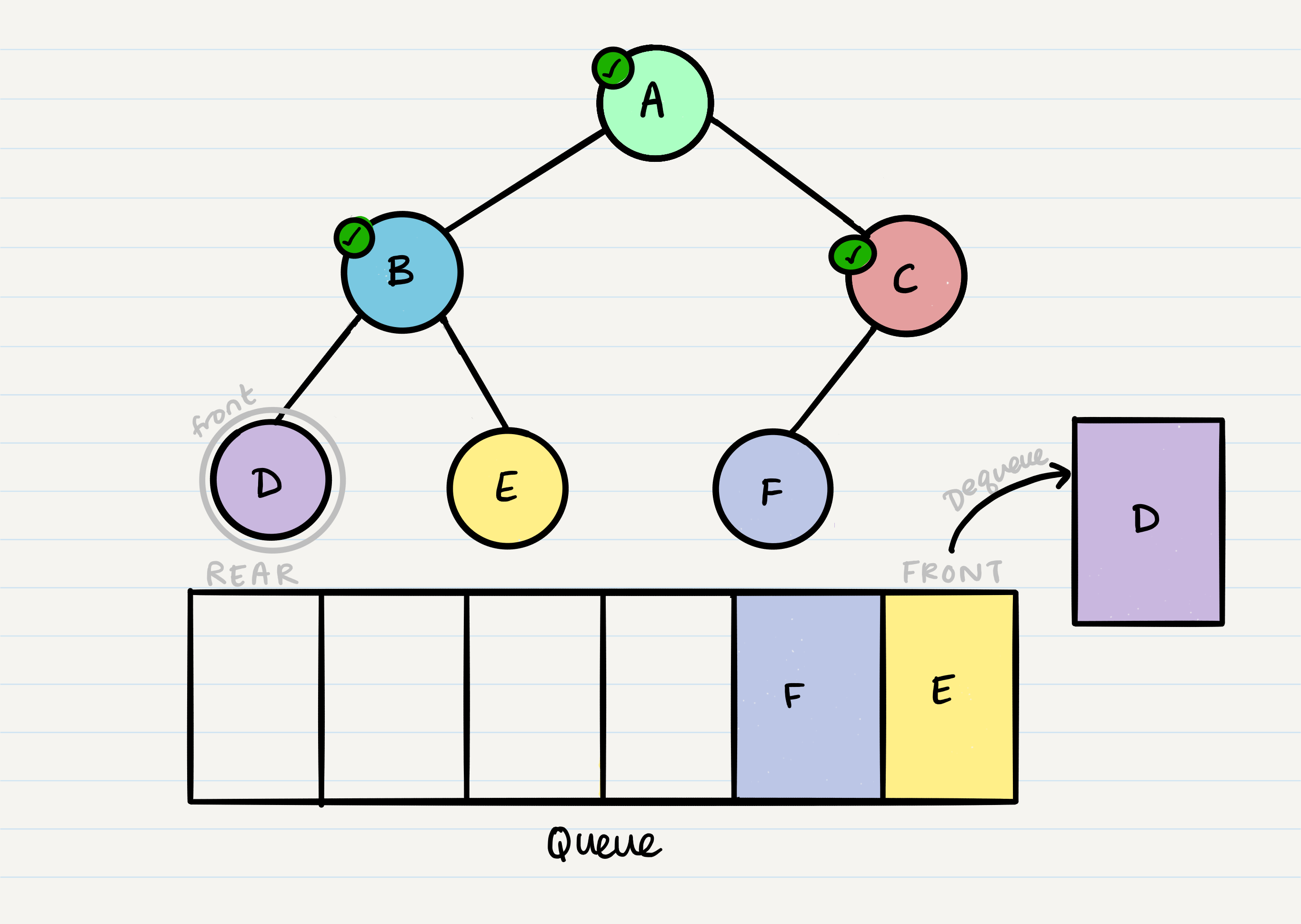

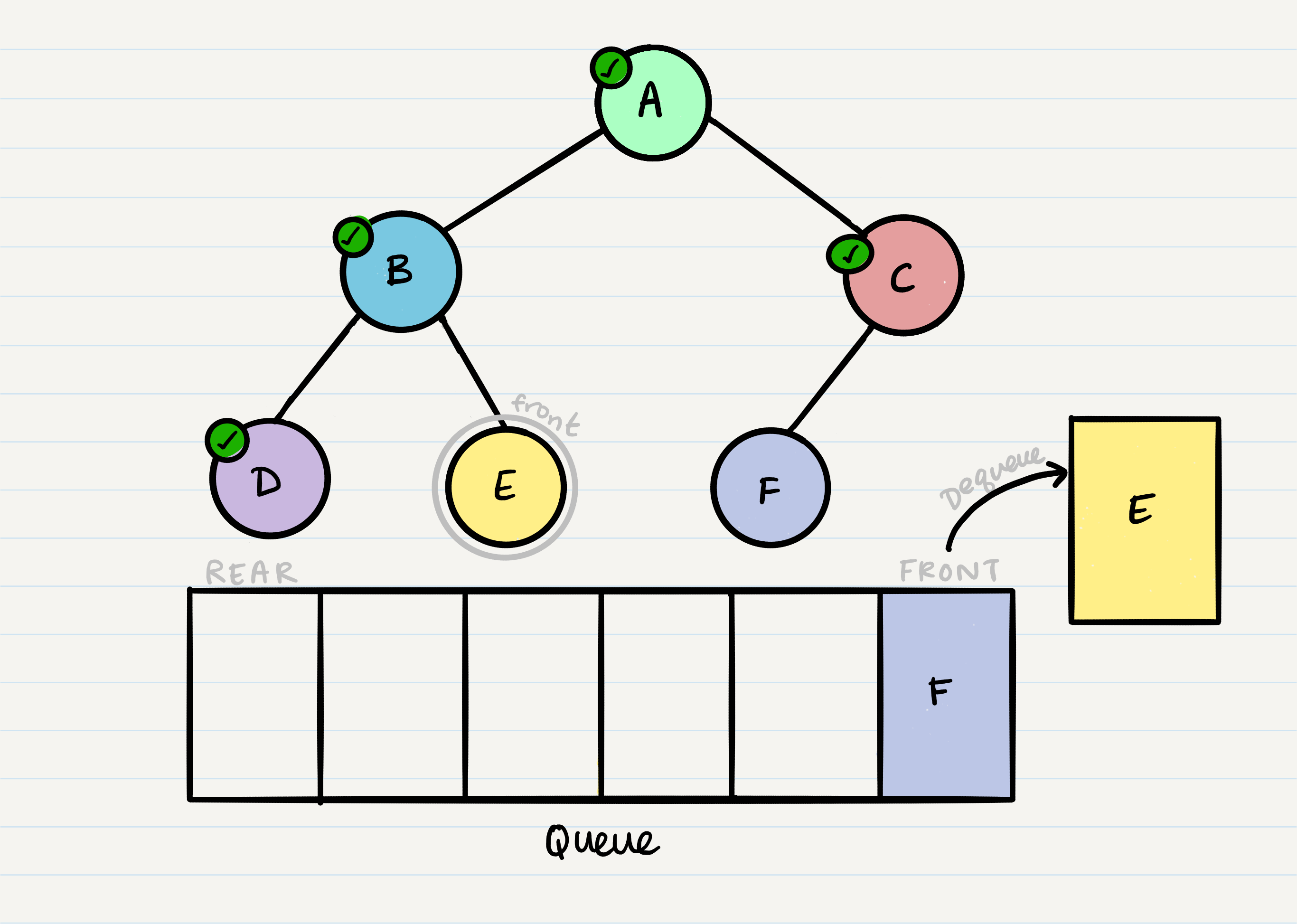

And we continue onwards. When we reach a node that doesn’t have any children, we just dequeue it without any further enqueue.

Pseudocode

Here is the pseudocode, utilizing a built-in queue to implement a breadth first traversal.

ALGORITHM breadthFirst(root)

// INPUT <-- root node

// OUTPUT <-- front node of queue to console

Queue breadth <-- new Queue()

breadth.enqueue(root)

while breadth.peek()

node front = breadth.dequeue()

OUTPUT <-- front.value

if front.left is not NULL

breadth.enqueue(front.left)

if front.right is not NULL

breadth.enqueue(front.right)

Binary Tree Vs K-ary Trees

In all of our examples, we’ve been using a Binary Tree. Trees can have any number of children per node, but Binary Trees restrict the number of children to two (hence our left and right children).

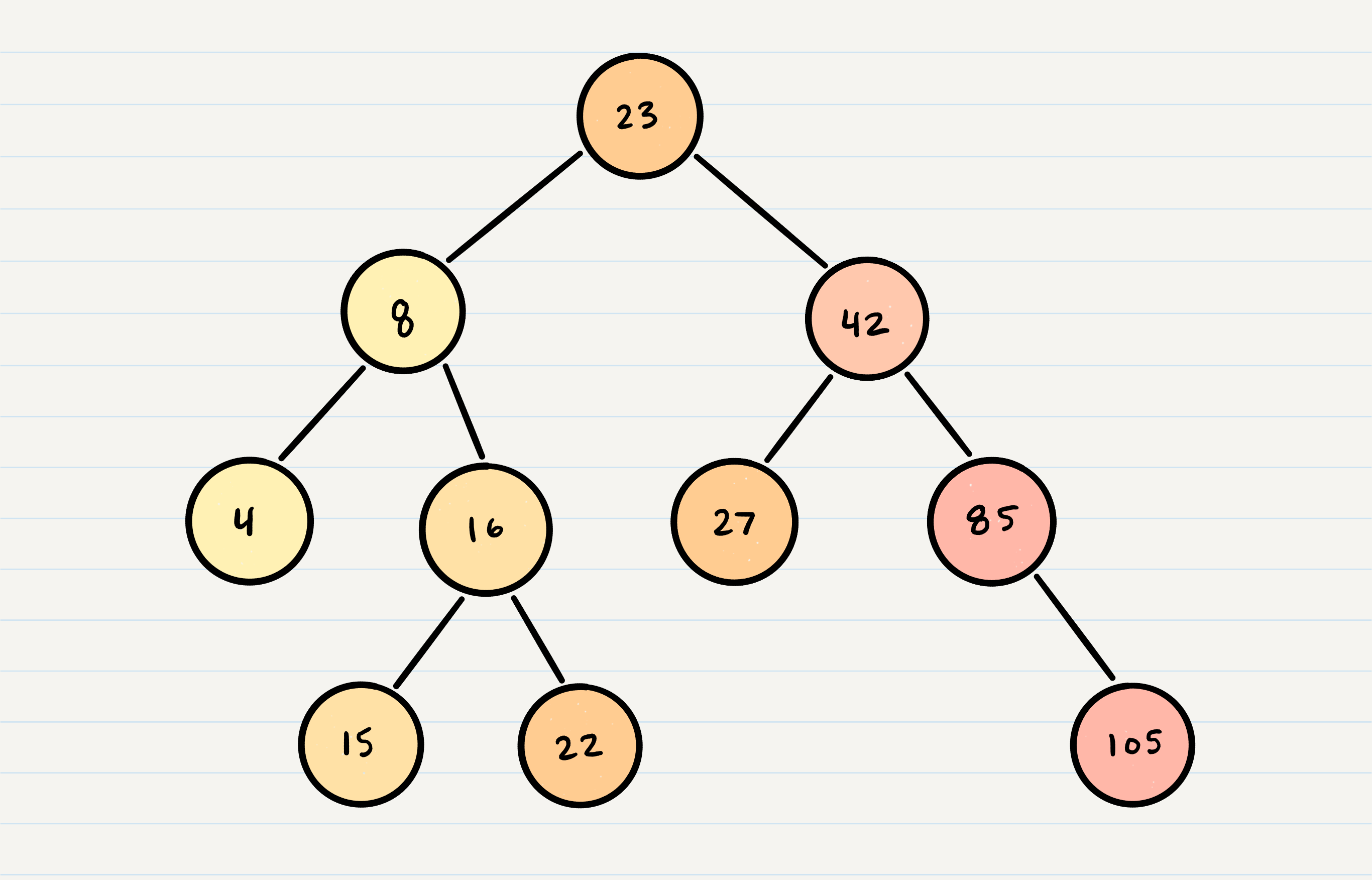

There is no specific sorting order for a binary tree. Nodes can be added into a binary tree wherever space allows. Here is what a binary tree looks like:

Binary Tree

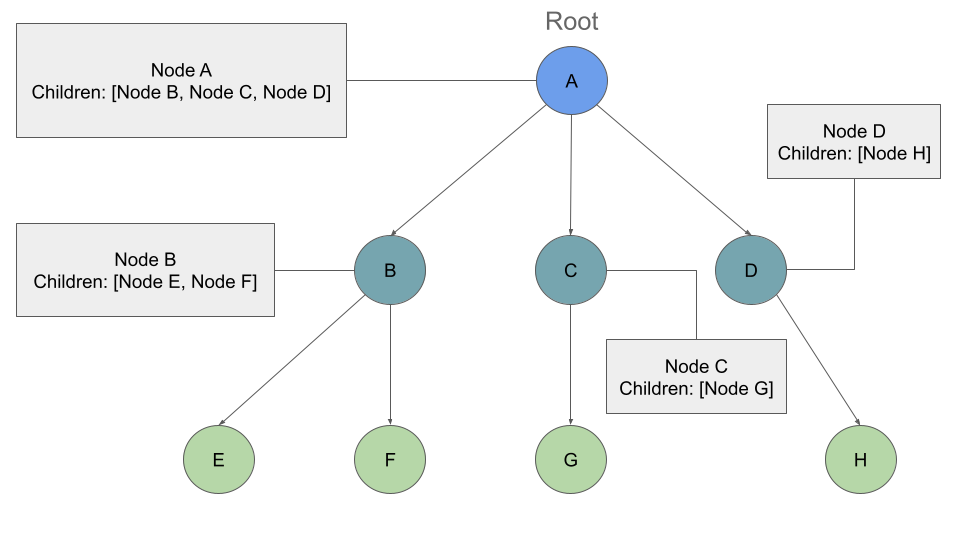

K-ary Trees If Nodes are able have more than 2 child nodes, we call the tree that contains them a K-ary Tree. In this type of tree we use K to refer to the maximum number of children that each Node is able to have.

Breadth First Traversal Traversing a K-ary tree requires a similar approach to the breadth first traversal. We are still pushing nodes into a queue, but we are now moving down a list of children of length k, instead of checking for the presence of a left and a right child.

If we traversed this tree Breadth First we should see the output:

Output: A, B, C, D, E, F, G, H

We will still start at the root Node, and we will add it to our queue:

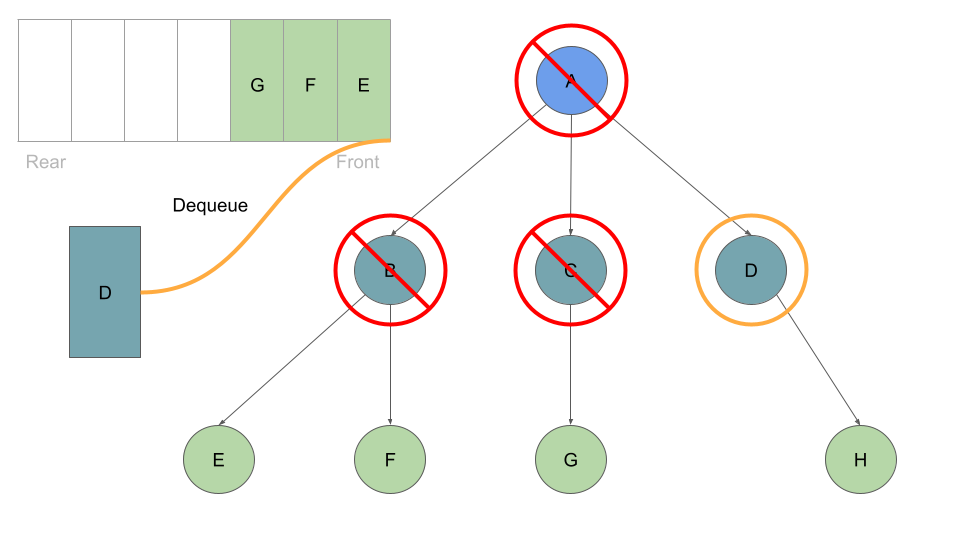

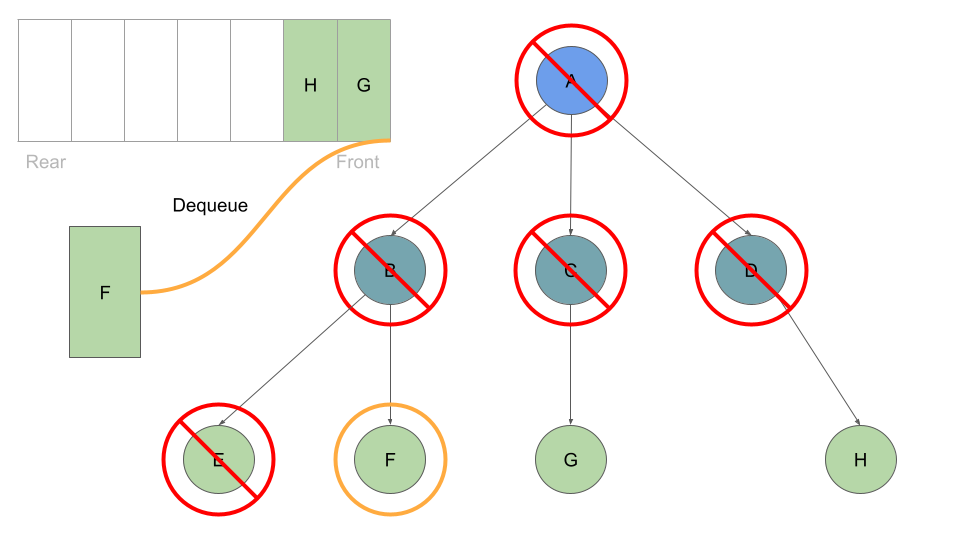

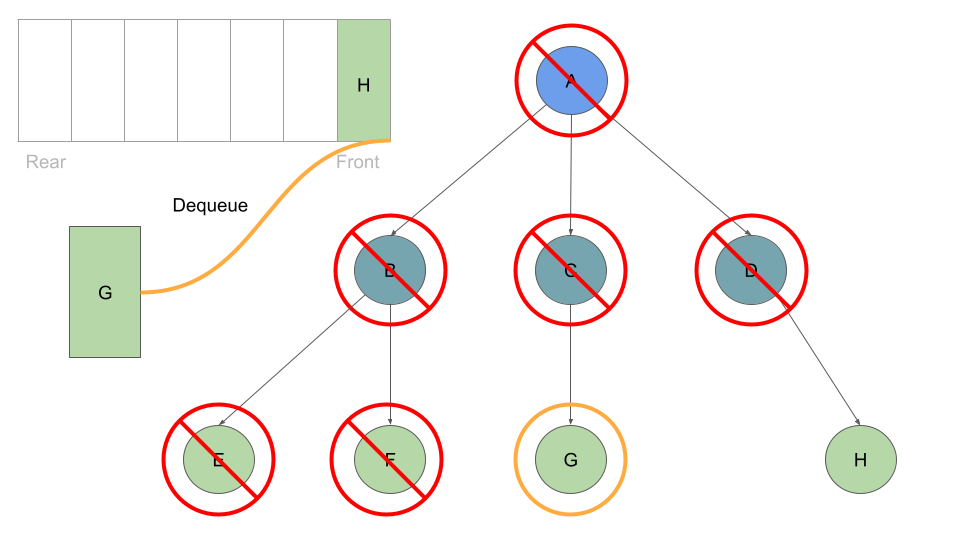

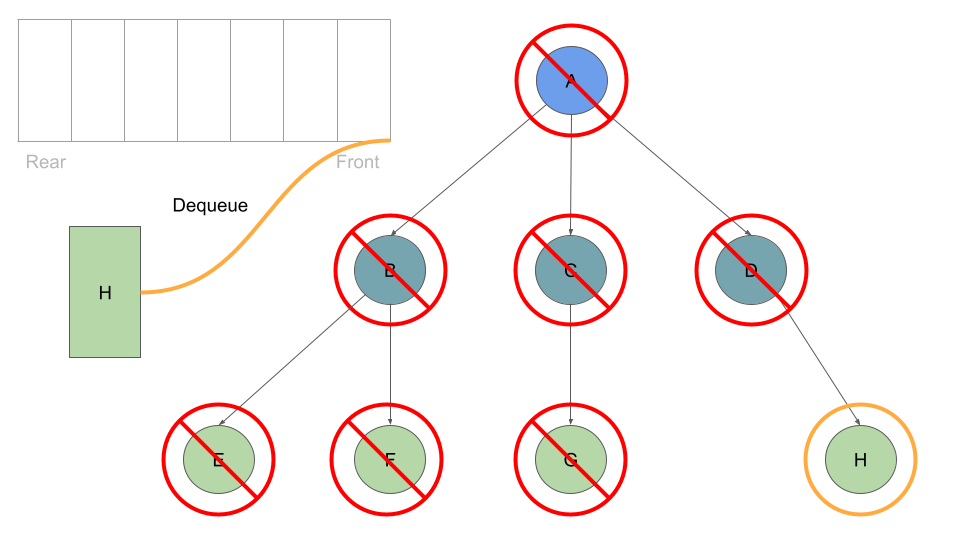

Much like before, as long as we have a node in our queue we can dequeue:

With every Node we dequeue, we check it’s list of childre and enqueue each one:

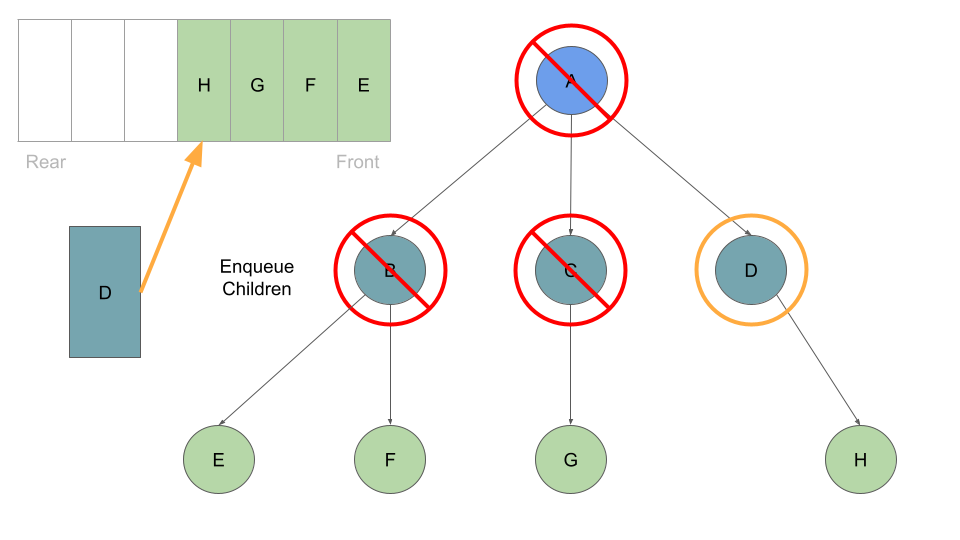

Once these are queued up, can move on to Node B at the front of the queue, which we can dequeue followed by enqueing Node B’s children:

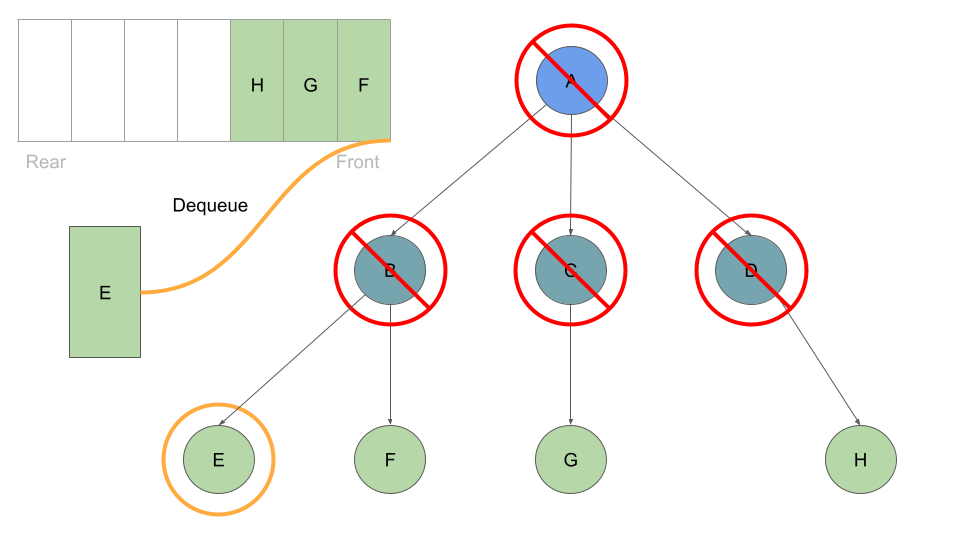

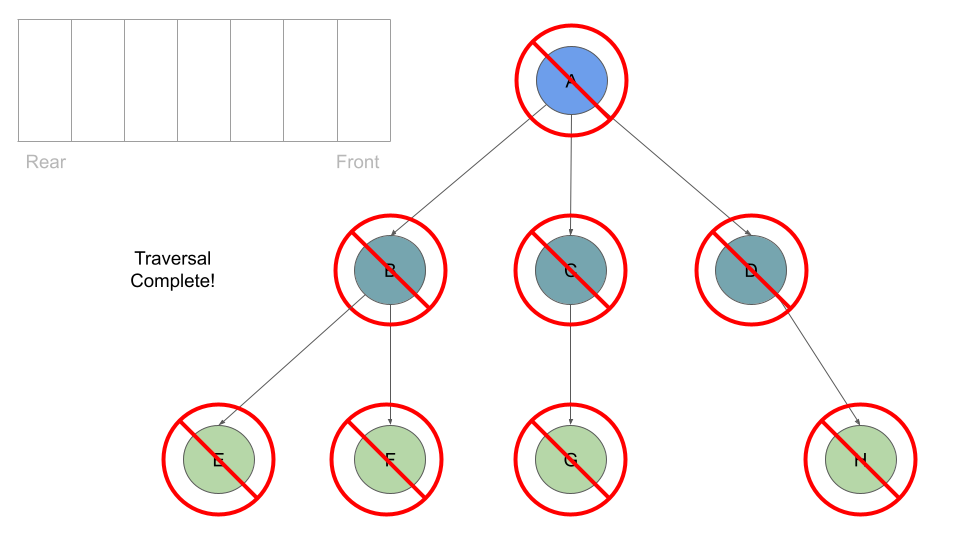

This process of dequeuing and processing the Nodes at the front of the queue, followed by enqueing the current Node’s children continues until our queue is empty of child Nodes:

Pseudocode

This process is very similar to our binary tree traversal, but now we check a list of children instead of a left and right child properties. It should look something like this:

ALGORITHM breadthFirst(root)

// INPUT <-- root node

// OUTPUT <-- front node of queue to console

Queue breadth <-- new Queue()

breadth.enqueue(root)

while breadth.peek()

node front = breadth.dequeue()

OUTPUT <-- front.value

for child in front.children

breadth.enqueue(child)

Adding a node

Because there are no structural rules for where nodes are “supposed to go” in a binary tree, it really doesn’t matter where a new node gets placed.

One strategy for adding a new node to a binary tree is to fill all “child” spots from the top down. To do so, we would leverage the use of breadth first traversal. During the traversal, we find the first node that does not have all it’s children filled, and insert the new node as a child. We fill the child slots from left to right.

In the event you would like to have a node placed in a specific location, you need to reference both the new node to create, and the parent node upon which the child is attached to.

Big O

The Big O time complexity for inserting a new node is O(n). Searching for a specific node will also be O(n). Because of the lack of organizational structure in a Binary Tree, the worst case for most operations will involve traversing the entire tree. If we assume that a tree has n nodes, then in the worst case we will have to look at n items, hence the O(n) complexity.

The Big O space complexity for a node insertion using breadth first insertion will be O(w), where w is the largest width of the tree. For example, in the above tree, w is 4.

A “perfect” binary tree is one where every non-leaf node has exactly two children. The maximum width for a perfect binary tree, is 2^(h-1), where h is the height of the tree. Height can be calculated as log n, where n is the number of nodes.

Binary Search Trees

A Binary Search Tree (BST) is a type of tree that does have some structure attached to it. In a BST, nodes are organized in a manner where all values that are smaller than the root are placed to the left, and all values that are larger than the root are placed to the right.

Here is how we would change our Binary Tree example into a Binary Search Tree:

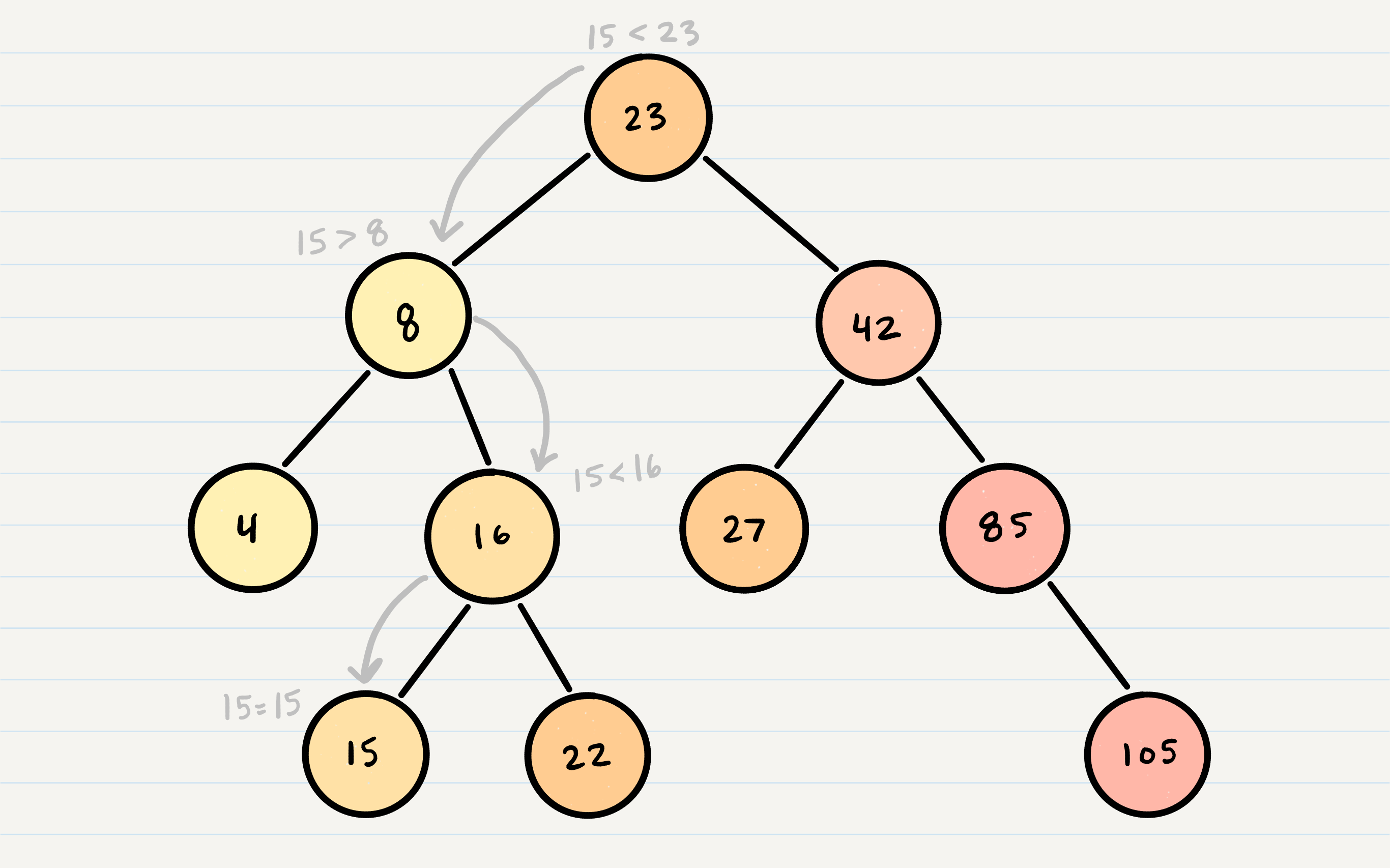

Searching a BST

Searching a BST can be done quickly, because all you do is compare the node you are searching for against the root of the tree or sub-tree. If the value is smaller, you only traverse the left side. If the value is larger, you only traverse the right side.

Let’s say we are searching 15. We start by comparing the value 15 to the value of the root, 23.

15 < 23, so we traverse the left side of the tree. We then treat 8 as our new “root” to compare against.

15 > 8, so we traverse the right side. 16 is our new root.

15 < 16, so we traverse the left side. And aha! 15 is our new root and also a match with what we were searching for.

The best way to approach a BST search is with a while loop. We cycle through the while loop until we hit a leaf, or until we reach a match with what we’re searching for.

Big O The Big O time complexity of a Binary Search Tree’s insertion and search operations is O(h), or O(height). In the worst case, we will have to search all the way down to a leaf, which will require searching through as many nodes as the tree is tall. In a balanced (or “perfect”) tree, the height of the tree is log(n). In an unbalanced tree, the worst case height of the tree is n.

The Big O space complexity of a BST search would be O(1). During a search, we are not allocating any additional space.

© Code Fellows 2021